MATHEMATICS

FOR

THE PRACTICAL MAN

EXPLAINING SIMPLY AND QUICKLY

ALL THE ELEMENTS OF

ALGEBRA, GEOMETRY, TRIGONOMETRY,

LOGARITHMS, COÖRDINATE

GEOMETRY, CALCULUS

WITH ANSWERS TO PROBLEMS

BY

GEORGE HOWE, M.E.

ILLUSTRATED

ELEVENTH THOUSAND

NEW YORK

D. VAN NOSTRAND COMPANY

25 Park Place

1918

i

Copyright, 1913, by

D. VAN NOSTRAND COMPANY

Copyright, 1915, by

D. VAN NOSTRAND COMPANY

𝔖𝔱𝔞𝔫𝔥𝔬𝔭𝔢 𝔓𝔯𝔢𝔰𝔰

F. H. GILSON COMPANY

BOSTON. U.S.A.

ii

Dedicated To

𝔅𝔯𝔬𝔴𝔫 𝔄𝔶𝔯𝔢𝔰, 𝔓𝔥.𝔇.

PRESIDENT OF THE UNIVERSITY OF TENNESSEE

“MY GOOD FRIEND AND GUIDE.”

iii

PREFACE

In preparing this work the author has been prompted

by many reasons, the most important of which are:

The dearth of short but complete books covering the

fundamentals of mathematics.

The tendency of those elementary books which “begin

at the beginning” to treat the subject in a popular rather

than in a scientific manner.

Those who have had experience in lecturing to large

bodies of men in night classes know that they are composed

partly of practical engineers who have had considerable

experience in the operation of machinery, but no

scientific training whatsoever; partly of men who have devoted

some time to study through correspondence schools

and similar methods of instruction; partly of men who

have had a good education in some non-technical field of

work but, feeling a distinct calling to the engineering

profession, have sought special training from night lecture

courses; partly of commercial engineering salesmen, whose

preparation has been non-technical and who realize in this

fact a serious handicap whenever an important sale is to

be negotiated and they are brought into competition with

the skill of trained engineers; and finally, of young men

leaving high schools and academies anxious to become

engineers but who are unable to attend college for that

purpose. Therefore it is apparent that with this wide

iv

difference in the degree of preparation of its students any

course of study must begin with studies which are quite

familiar to a large number but which have been forgotten

or perhaps never undertaken by a large number of others.

And here lies the best hope of this textbook. “It begins

at the beginning,” assumes no mathematical knowledge beyond

arithmetic on the part of the student, has endeavored

to gather together in a concise and simple yet accurate and

scientific form those fundamental notions of mathematics

without which any studies in engineering are impossible,

omitting the usual diffuseness of elementary works, and

making no pretense at elaborate demonstrations, believing

that where there is much chaff the seed is easily lost.

I have therefore made it the policy of this book that

no technical difficulties will be waived, no obstacles circumscribed

in the pursuit of any theory or any conception.

Straightforward discussion has been adopted; where

obstacles have been met, an attempt has been made to

strike at their very roots, and proceed no further until

they have been thoroughly unearthed.

With this introduction, I beg to submit this modest

attempt to the engineering world, being amply repaid if,

even in a small way, it may advance the general knowledge

of mathematics.

GEORGE HOWE.

New York, September, 1910.

CHAPTER I

v

TABLE OF CONTENTS

| Chapter | Page | |

|---|---|---|

| I. | Fundamentals of Algebra. Addition and Subtraction | 1 |

| II. | Fundamentals of Algebra. Multiplication and Division, I | 7 |

| III. | Fundamentals of Algebra. Multiplication and Division, II | 12 |

| IV. | Fundamentals of Algebra. Factoring | 21 |

| V. | Fundamentals of Algebra. Involution and Evolution | 25 |

| VI. | Fundamentals of Algebra. Simple Equations | 29 |

| VII. | Fundamentals of Algebra. Simultaneous Equations | 41 |

| VIII. | Fundamentals of Algebra. Quadratic Equations | 48 |

| IX. | Fundamentals of Algebra. Variation | 55 |

| X. | Some Elements of Geometry | 61 |

| XI. | Elementary Principles of Trigonometry | 75 |

| XII. | Logarithms | 85 |

| XIII. | Elementary Principles of Coördinate Geometry | 95 |

| XIV. | Elementary Principles of the Calculus | 110 |

001

Mathematics

CHAPTER I

Fundamentals of Algebra

Addition and Subtraction

As an introduction to this chapter on the fundamental

principles of algebra, I will say that it is absolutely

essential to an understanding of engineering that the

fundamental principles of algebra be thoroughly digested

and redigested,—in short, literally soaked into one’s

mind and method of thought.

Algebra is a very simple science—extremely simple

if looked at from a common-sense standpoint. If not

seen thus, it can be made most intricate and, in fact,

incomprehensible. It is arithmetic simplified,—a short

cut to arithmetic. In arithmetic we would say, if one

hat costs 5 cents, 10 hats cost 50 cents. In algebra

we would say, if one

002

to represent another thing,

Definition of a Symbol. — A symbol is some letter by

which it is agreed to represent some object or thing.

When a problem is to be worked in algebra, the first

thing necessary is to make a choice of symbols, namely,

to assign certain letters to each of the different objects

concerned with the problem,—in other words, to get

up a code. When this code is once established it must

be rigorously maintained; that is, if, in the solution of

any problem or set of problems, it is once stipulated

that

003

Positivity and Negativity. — Now, in algebraic thought,

not only do we use symbols to represent various objects

and things, but we use the signs plus (+) or minus (−)

before the symbols, to indicate what we call the positivity

or negativity of the object.

Addition and Subtraction. — Algebraically, if, in going

over his stock and accounts, a merchant finds that

he has 4 tables in stock, and on glancing over his

books finds that he owes 3 tables, he would represent

the 4 tables in stock by such a form as

Suppose the following to be the inventory of a certain

quantity of stock:

004

on grouping

reduces to

.

This process of gathering together and simplifying a

collection of terms having different signs is what we

call in algebra addition and subtraction. Nothing is

more simple, and yet nothing should be more thoroughly

understood before proceeding further. It is obviously

impossible to add one table to one chair and thereby

get two chairs, or one book to one hat and get two

books; whereas it is perfectly possible to add one book

to another book and get two books, one chair to another

chair and thereby get two chairs.

Rule. — Like symbols can be added and subtracted, and

only like symbols.

005

Coefficients. — In any term such as

Algebraic Expressions. — An algebraic expression consists

of two or more terms; for instance,

006

wherever it is met in a problem, and thus simplify the

manipulation or handling of it.

When there is no sign before the first term of an

expression the plus (+) sign is intended.

To subtract one quantity from another, change the

sign and then group the quantities into one term, as just

explained. Thus: to subtract

PROBLEMS

Simplify the following expressions:

1..

2..

3..

4..

5..

6..

We have seen how the use of algebra simplifies the

operations of addition and subtraction, but in multiplication

and division this simplification is far greater, and

the great weapon of thought which algebra is to become

to the student is now realized for the first time. If the

student of arithmetic is asked to multiply one foot by

one foot, his result is one square foot, the square foot

being very different from the foot. Now, ask him to

multiply one chair by one table. How can he express

the result? What word can he use to signify the result?

Is there any conception in his mind as to the appearance

of the object which would be obtained by multiplying

one chair by one table? In algebra all this is

simplified. If we represent a table by

008

form is carried without any further thought being given

to it.

Exponents. — The multiplication of

Now, suppose

Rule. — The multiplication by each other of symbols

representing similar objects is accomplished by adding

their exponents.

Identity of Symbols. — Now, in the foregoing it must

be clearly seen that the combined symbol

009

foot. ,

to simplify it we could group together the

Suppose we have

Division. — Just as when in arithmetic we write

down

010

If

Negative Exponents. — But there is a more scientific

and logical way of explaining division as the inverse

of multiplication, and it is thus: Suppose we have the

fraction

011

be carefully considered and thought over by the pupil,

for it is of great importance. Take such an expression

as PROBLEMS

Simplify the following:

1..

2..

3..

4..

5..

6..

7..

8..

9..

10..

HAVING illustrated and explained the principles of

multiplication and division of algebraic terms, we will

in this lecture inquire into the nature of these processes

as they apply to algebraic expressions. Before doing

this, however, let us investigate a little further into the

principles of fractions.

Fractions. — We have said that the fraction

Rule. — The multiplication of a fraction by any quantity

is accomplished by multiplying its numerator by

that quantity; thus,

013

quantity, we multiply its denominator by that quantity.

Thus, the fraction

Multiplying two fractions by each other is accomplished

by multiplying their numerators together and

multiplying their denominators together. Thus,

Suppose it is desired to add the fraction

014

which in this case is 6, viz.:

Law of Signs. — Like signs multiplied or divided give

+ and unlike signs give −. Thus:

gives ,

alsogives ,

015

whilegives

orgives ;

furthermoredivided by gives ,

anddivided by gives

whiledivided by gives

ordivided by gives .

Multiplication of an Algebraic Expression by a

Quantity. — As previously said, an algebraic expression

consists of two or more terms.

Rule. — An algebraic expression must be treated as a

unit. Whenever it is multiplied or divided by any quantity,

each term of the expression must be multiplied or

divided by that quantity. For example: Multiplying

016

the expression

Division of an Algebraic Expression by a Quantity. —

Dividing the expression

017

Multiplication of One Algebraic Expression by Another. —

It is frequently desired to multiply an algebraic

expression not only by a single term but by another

algebraic expression consisting of two or more terms, in

which case the first expression is multiplied throughout

by each term of the second expression. The terms which

result from this operation are then collected together

by addition and subtraction and the result expressed in

the simplest manner possible. Suppose it were desired

to multiply

Workup 3-1

a + b

c + d

_______

ac + bc

ad + bd

____________________

ac + bc + ad + bd

Workup 3-1

Again, let us multiply

Workup 3-2

and we have

Workup 3-3

2a + b − 3c

a + 2b − c

____________________

2a² + ab − 3ac

4ab + 2b² − 6bc

− 2ac − bc + 3c²

_____________________________________

Workup 3-2

Workup 3-3

018

The Division of one Algebraic Expression by Another. —

This is somewhat more difficult to explain and understand

than the foregoing. In general it may be said

that, suppose we are required to divide the expression

Workup 3-4

6a² + 17ab + 12b² | 3a + 4b

|_________

6a² + 8ab 2a + 3b

____________________

9ab + 12b²

9ab + 12b²

Workup 3-4

This process should be studied and thoroughly understood

by the student.

019

PROBLEMS

Solve the following problems:

1. Multiply the fractionby the quantity .

2. Divide the fractionby the quantity .

3. Multiply the fractionby the fraction by the fraction .

4. Multiply the expressionby the quantity .

5. Divide the expressionby the quantity .

6. Multiply the expressionby the expression .

7. Multiply the expressionby the expression .

8. Divide the expressionby .

9. Divide the expressionby .

10. Multiply the fractionby .

11. Multiply the fractionby by .

12. Multiply the fractionby by .

020

13. Add together the fractions.

14. Add together the fractions.

1S. Add together the fractions.

16. Add together the fractions.

Definition of a Factor. — A factor of a quantity is

one of the two or more parts which when multiplied

together give the quantity. A factor is an integral

part of a quantity, and the ability to divide and subdivide

a quantity, be it a single term or a whole expression,

into those factors whose multiplication has created

it, is very valuable.

Factoring. — Suppose we take the number 6. Its

factors are readily detected as 2 and 3. Likewise the

factors of 10 are 5 and 2. The factors of 18 are 9 and

2; or, better still,

The factors of an expression consisting of two or more

terms, however, are not so readily seen and sometimes

require considerable ingenuity for their detection. Suppose

we have an algebraic expression in which all of

022

the terms have one or more common factors,—that is,

that one or more like factors appear in the make-up of

each term. It is often desirable in this case to remove

the common factors from the several terms, and in

order to do this without changing the value of any of

the terms, the common factor or factors are placed

outside of a parenthesis and the terms from which they

have been removed placed within the parenthesis in

their simplified form. Thus, in the algebraic expression

Still further suppose we have

we have

,

or,

.

023

Now, suppose we have the expression

The product of the sum and difference of two terms

such as

By trial it is often easy to discover the factors of

algebraic expressions; for example,

PROBLEMS

Factor the following:

1..

2..

3..

4..

5..

6..

7..

024

8..

9..

10..

11..

12..

13..

14..

15..

16..

17..

18..

19..

20..

21..

22..

23..

24..

We have in a previous chapter discussed the process

by which we can raise an algebraic term and even a

whole algebraic expression to any power desired, by

multiplying it by itself. Let us now investigate the

method of finding the square root and the cube root

of an algebraic expression, as we are frequently called

upon to do.

The square root of any term such as

026

of

Square Root of an Algebraic Expression. — Suppose

we multiply the expression

Workup 5-1

a² + 2ab + b² | a + b

a² |________

_______________

2a + b | 2ab + b²

| 2ab + b²

|__________

Workup 5-1

027

Likewise we see that the square root of

Workup 5-2

4a² + 12ab + 9b² | 2a + 3b

4a² |________

____________________

4a + 3b | 2 ab + 9b²

| 2 ab + 9b²

|______________

Workup 5-2

The Cube Root of an Algebraic Expression. — If we

multiply

028

a³ + 3a²b + 3ab² + b² | a + b

a³ |_______

____________________________

3a² + 3ab + b² | 3a²b + 3ab² + b²

| 3a²b + 3ab² + b²

|_____________________

Workup 5-3

Likewise the cube root of

Workup 5-4

27x³ + 27x² + 9x + 1 | 3x+ 1

27x³ |_______

_______________________

27x² + 9x + 1 | 27x² + 9x + 1

| 27x² + 9x + 1

|_________________

Workup 5-4

PROBLEMS

Find the square root of the following expressions:

1..

2..

3..

4..

5..

Find the cube root of the following expressions:

1..

2..

An equation is the expression of the equality of two

things; thus,

,

then

and

.

Similarly, if one side of an equation is squared, the

other side of the equation must be squared in order to

030

retain the equality. In general, whatever is done to

one side of an equation must also be done to the other

side in order to retain the equality of both sides. The

logic of this is self-evident.

Transposition. — Suppose we have the equation

may be transposed into the equation

,

or into the form

,

or into the form

.

Any term may be transposed from one side of an equation

to the other simply by changing its sign.

Adding or Subtracting Two Equations. — When two

equations are to be added to one another their corresponding

031

sides are added to one another; thus,

Multiplying or Dividing Two Equations by one Another. — When

two equations are multiplied or divided

by one another their corresponding sides must be multiplied

or divided by one another; thus,

Solution of an Equation. — Suppose we have such an

equation as

.

Now, collecting the like terms, this becomes

.

The next step is to divide the equation through by the

coefficient of x, namely, 2. Dividing the left-hand

032

side by 2, we have x. Dividing the right-hand side

by 2, we have 7. Our equation, therefore, has resolved

itself into

.

We therefore have the value of x. Substituting this

value in the original equation, namely,

,

we see that the equation becomes

,

or

,

which proves the result.

The process above described is the general method of

solving for an unknown quantity in a simple equation.

Let us now take the equation

.

This equation contains two unknown quantities, namely,

c and x, either of which we may solve for. x is usually,

however, chosen to represent the unknown quantity,

whose value we wish to find, in an algebraic expression;

in fact, x, y and z are generally chosen to represent

unknown quantities. Let us solve for x in the above

equation. Again we group the two terms containing

x on one side of the equation by themselves and all

other terms on the other side, and we have

.

033

On the left-hand side of the equation we have two terms

containing x as a factor. Let us factor this expression

and we have

.

Dividing through by the coefficient of x, which is the

parenthesis in this case, just as simple a coefficient to

handle as any other, and we have

.

This final result is the complete solution of the equation

as to the value of x, for we have x isolated on

one side of the equation by itself, and its value on the

other side. In any equation containing any number of

unknown quantities represented by symbols, the complete

solution for the value of any one of the unknowns is

accomplished when we have isolated this unknown on one

side of the equation by itself. This is, therefore, the whole

object of our solution.

It is true that the value of a above shown still contains

an unknown quantity, c. Suppose the numerical

value of c were now given, we could immediately find

the corresponding numerical value of x; thus, suppose c

were equal to 2, we would have

or,.

034

This is the numerical value of x, corresponding to the

numerical value 2 of c. It 4 had been assigned as

the numerical value of c we should have

.

Clearing of Fractions. — The above simple equations

contained no fractions. Suppose, however, that we are

asked to solve the equation

.

Manifestly this equation cannot be treated at once in

the manner of the preceding example. The first step

in solving such an equation is the removal of all the

denominators of the fractions in the equation, this

step being called the Clearing of Fractions.

As previously seen, in order to add together the

fractions

Workup 6-1

035

not always the least common denominator. The least

common denominator, being the smallest common denominator,

is always desirable in preference to a larger

number; but some ingenuity is needed frequently in

detecting it. The old rule of withdrawing all factors

common to at least two denominators and multiplying

them together, and then by what is left of the denominators,

is probably the easiest and simplest way to proceed.

Thus, suppose we have the denominators 6, 8,

9 and 4. 3 is common to both 6 and 9, leaving respectively

2 and 3. 2 is common to 2, 8 and 4, leaving

respectively 1, 4 and 2, and still further common to 4

and 2. Finally, we have removed the common factors

3, 2 and 2, and we have left in the denominators 1, 2,

3 and 1. Multiplying all of these together we have

72, which is the Least Common Denominator of these

numbers, viz.:

3 | 6, 8, 9, 4

|____________

2 | 2, 8, 3, 4

|____________

2 | 1, 4, 3, 2

|____________

1, 2, 3, 1

Workup 6-1

.

Having determined the Least Common Denominator,

or any common denominator for that matter, the next

step is to multiply each denominator by such a quantity

as will change it into the Least Common Denominator.

If the denominator of a fraction is multiplied by any

036

quantity, as we have previously seen, the numerator

must be multiplied by that same quantity, or the value

of the fraction is changed. Therefore, in multiplying

the denominator of each fraction by a quantity, we

must also multiply the numerator. Returning to the

equation which we had at the outset, namely,

,

or

,

or

,

or

.

Again, let us now take the equation

.

037

The least common denominator will at once be seen to

be

.

Canceling all denominators, we then have

.

Transposing, we have

.

Taking x as a common factor out of both of the terms

in which it appears, we have

.

Dividing through by the parenthesis, we have

This is the value of x. If some numerical value is

given to c, such as 2, for instance, we can then find

the corresponding numerical value of x by substituting

the numerical value of c in the above, and we have

.

In this same manner all equations in which fractions

appear are solved.

038

PROBLEMS

Suppose we wish to make use of algebra in the solution

of a simple problem usually worked arithmetically,

taking, for example, such a problem as this: A man purchases

a hat and coat for $15.00, and the coat costs

twice as much as the hat. How much did the hat cost?

We would proceed as follows: Let x equal the cost of

the hat. Since the coat cost twice as much as the hat,

then

Solve the following equations:

1..

2..

3.. Find the numerical value of x if .

4..

5..

6.. Find the numerical value of x if .

039

7.. Find the numerical value of x if .

8..

9..

10..

11. Multiplyby .

12. Multiplyby .

13. Divideby .

14. Divideby .

15. Addto .

16. Addto .

17. Addto .

18. Subtractfrom .

19. Subtractfrom .

20. Subtractfrom .

21. Multiplyby .

22. Solve the equation.

23. If a coat cost one-half as much as a gun and twice as much as a hat, and all cost together $100, what is the cost of each?

040

24. The value of a horse is $15 more than twice the value of a carriage, and the cost of both is $1000; what is the cost of each?

25. One-third of Anne’s age is 5 years less than one-half plus 2 years; what is her age?

26. A merchant has 10 more chairs than tables in stock. He sells four of each and adding up stock finds that he now has twice as many chairs as tables. How many of each did he have at first?

041

CHAPTER VII

Fundamentals of Algebra

Simultaneous Equations

As seen in the previous chapter, when we have a

simple equation in which only one unknown quantity

appears, such, for instance, as x, we can, by algebraic

processes, at once determine the numerical value

of this unknown quantity. Should another unknown

quantity, such as c, appear in this equation, in order

to determine the value of x some definite value must

be assigned to c. However, this is not always possible.

An equation containing two unknown quantities

represents some manner of relation between these

quantities. If two separate and distinct equations representing

two separate and distinct relations which exist

between the two unknown quantities can be found,

then the numerical values of the unknown quantities

become fixed, and either one can be determined without

knowing the corresponding value of the other. The

two separate equations are called simultaneous equations,

since they represent simultaneous relations between

the unknown quantity. The following is an

example:

042

.

.

The first equation represents one relation between

.

Likewise in the second equation we have

.

These two values of

or,,

,

,

,

.

Now, this is the value of

043

such as the first equation, .

Transposing,

,

.

Here, then, we have found the values of both

The simultaneous equations above given might have

been solved likewise by simply adding both equations

together, thus:

Adding

and

,

we have

.

Here

,

.

Both of these processes are called elimination, the

principal object in solving simultaneous equations being

the elimination of unknown quantities until some equation

is obtained in which only one unknown quantity

appears.

We have seen that by simply adding two equations

044

we have eliminated one of the unknowns. But suppose

the equations are of this type:

(1),

(2).

Now we can proceed to solve these equations in one of

two ways: first, to find the value of

.

Now, when this is subtracted from equation (I), thus:

________________

the terms in

or

,

therefore

.

Just as in order to find the value of two unknowns

two distinct and separate equations are necessary to

express relations between these unknowns, likewise to

find the value of the unknowns in equations containing

045

three unknown quantities, three distinct and separate

equations are necessary. Thus, we may have the

equations

(1),

(2),

(3).

We now combine any two of these equations, for instance

the first and the second, with the idea of eliminating

one of the unknown quantities, as

(4).

Now taking any other two of the equations, such as the

second and the third, and subtracting one from the other,

with a view to eliminating

(5).

We now have two equations containing two unknowns,

which we solve as before explained. For instance, adding

them, we have

,

.

Substituting this value of z in equation (4), we have

,

.

046

Substituting both of these values of z and y in equation

(1), we have

,

.

Thus we see that with three unknowns three distinct

and separate equations connecting them are necessary in

order that their values may be found. Likewise with

four unknowns four distinct and separate equations

showing relations between them are necessary. In each

case where we have a larger number than two equations,

we combine the equations together two at a time, each

time eliminating one of the unknown quantities, and,

using the resultant equations, continue in the same

course until we have finally resolved into one final

equation containing only one unknown. To find the

value of the other unknowns we then work backward,

substituting the value of the one unknown found in an

equation containing two unknowns, and both of these in

an equation containing three unknowns, and so on.

The solution of simultaneous equations is very important

and the student should practice on this subject

until he is thoroughly familiar with every one of these

steps.

PROBLEMS

Solve the following problems:

1.

.

047

2.

.

3.

.

4. Find the value of, y and z in the following equations:

,

,

.

5. Find the value of, y and z in the following equations:

,

,

.

6.,

.

7.if ,

.

8.,

.

9.,

if, .

THUS far we have handled equations where the

unknown whose value we were solving for entered the

equation in the first power. Suppose, however, that

the unknown entered the equation in the second power;

for instance, the unknown

.

In solving this equation in the usual manner we obtain

,

.

Taking the square root of both sides,

.

We first obtained the value of

.

We see that none of the processes thus far discussed

will do. We must therefore find some way of grouping

049

It consists as follows: Group together all terms in

.

Dividing through by the coefficient of

.

Adding to both sides the square of one-half of the

coefficient of

.

The left-hand side of this equation has now been made

into the perfect square of

.

Now taking the square root of both sides we have

.

050

Therefore, using the plus sign of 2, we have

.

Using the minus sign of 2 we have

.

The student will note that there must, in the nature of

the case, be two distinct and separate roots to a quadratic

equation, due to the plus and minus signs above

mentioned.

To recapitulate the preceding steps, we have:

(1) Group all the terms in

(2) Divide through by the coefficient of

(3) Add to both sides of the equation the square of

one-half of the coefficient of the

(4) Take the square root of both sides (the left-hand

side being a perfect square). Then solve as for a simple

equation in

Example: Solve for

,

,

,

,

,

.

051

Taking the square root of both sides we have

,

,

or ,

Example: Solve for

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

or

052

Solving an Equation which Contains a Root. — Frequently

we meet with an equation which contains a

square or a cube root. In such cases it is necessary to

get rid of the square or cube root sign as quickly as

possible. To do this the root is usually placed on one

side of the equation by itself, and then both sides are

squared or cubed, as the case may be, thus:

Example: Solve the equation

.

Solving for the root, we have

.

Now squaring both sides we have

or,,

,

.

In any event, our prime object is first to get the square-root

sign on one side of the equation by itself if possible,

so that it may be removed by squaring.

Or the equation may be of the type

.

Squaring both sides we have

053

Clearing fractions we have

PROBLEMS

Solve the following equations for the value of

1..

2..

3..

4..

5..

6..

7..

8..

9..

10..

11..

12..

13..

14..

15..

054

16..

17..

18..

19..

20..

21..

THIS is a subject of the utmost importance in the

mathematical education of the student of science. It

is one to which, unfortunately, too little attention is

paid in the average mathematical textbook. Indeed,

it is not infrequent to find a student with an excellent

mathematical training who has but vaguely grasped

the notions of variation, and still it is upon variation

that we depend for nearly every physical law.

Fundamentally, variation means nothing more than

finding the constants which connect two mutually

varying quantities. Let us, for instance, take wheat

and money. We know in a general way that the more

money we have the more wheat we can purchase.

This is a variation between wheat and money. But we

can go no further in determining exactly how many

bushels of wheat a certain amount of money will buy

before we establish some definite constant relation

between wheat and money, namely, the price per

bushel of wheat. This price is called the Constant of

the variation. Likewise, whenever two quantities are

varying together, the movement of one depending

absolutely upon the movement of the other, it is impossible

056

to find out exactly what value of one corresponds

with a given value of the other at any time,

unless we know exactly what constant relation subsists

between the two.

Where one quantity,

.

Now, wherever we have such a relation we can immediately

write

= some constant ,

.

If we observe closely two corresponding values of

Experimentation in a laboratory will enable us to

determine, not one, but a long series of corresponding

values of two varying quantities. This series of values

will give us an idea of the nature of their variation.

We may then write down the variation as above shown,

and solve for the constant. This constant establishes

the relation between

057

100 pounds on a wire of a certain length and size it

stretched one-tenth of an inch. On suspending 200

pounds he observes that it stretches two-tenths of an

inch. On suspending 300 pounds he observes that it

stretches three-tenths of an inch, and so on. He at

once sees that there is a constant relation between the

elongation and the weight producing it. He then

writes:

Elongationweight.

Elongation = some constantweight.

.

Now this is an equation. Suppose we substitute one of

the sets of values of elongation and weight, namely,

.3 of an inch and 300 lbs.

We have

.3 =.

Therefore

.

Now, this is an absolute constant for the stretch of that

wire, and if at any time we wish to know how much a

certain weight, say 500 lbs., will stretch that wire, we

simply have to write down the equation

.

Substituting

elong. =,

and we have

elong. =of an inch.

Thus, in general, the student will remember that where

two quantities vary as each other we can change this

variation, which cannot be handled mathematically,

058

into an equation which can be handled with absolute

definiteness and precision by simply inserting a constant

into the variation.

Inverse Variation. — Sometimes we have one quantity

increasing at the same rate that another decreases;

thus, the pressure on a certain amount of air increases

as its volume is decreased, and we write

,

then

,

Wherever one quantity increases as another decreases,

we call this an inverse variation, and we express it in the

manner above shown. Frequently one quantity varies

as the square or the cube or the fourth power of the

other; for instance, the area of a square varies as the

square of its side, and we write

,

or

.

Again, one quantity may vary inversely as the square of

the other, as, for example, the intensity of light, which

varies inversely as the square of the distance from its

source, thus:

,

or

,

059

Grouping of Variations. — Sometimes we have a

quantity varying as one quantity and also varying as

another quantity. In such cases we may group these

two variations into a single variation. Thus, we say

that

also,

,

then

or,

.

This is obviously correct; for, suppose we say that the

weight which a beam will sustain in end-on compression

varies directly as its width, also directly as its depth,

we see at a glance that the weight will vary as the

cross-sectional area, which is the product of the width

by the depth.

Sometimes we have such variations as this:

,

also

,

then

.

This is practically the same as the previous case, with

the exception that instead of two direct variations we

have one direct and one inverse variation.

There is much interesting theory in variation, which,

however, is unimportant for our purposes and which

060

I will therefore omit. If the student thoroughly masters

the principles above mentioned he will find them

of inestimable value in comprehending the deduction

of scientific equations.

PROBLEMS

1. Ifand we have a set of values showing that when , , what is the constant of this variation?

2. If, and the constant of the variation is 2205, what is the value of when = 5?

3.; also , or, . If we find that when , then and , what is the constant of this variation?

4.. The constant of the variation equals 12. What is the value of when = 2 and = 8?

In this chapter I will attempt to explain briefly some

elementary notions of geometry which will materially

aid the student to a thorough understanding of many

physical theories. At the start let us accept the following

axioms and definitions of terms which we will

employ.

Axioms and Definitions:

I. Geometry is the science of space.

II. There are only three fundamental directions or

dimensions in space, namely, length, breadth and depth.

III. A geometrical point has theoretically no dimensions.

IV. A geometrical line has theoretically only one

dimension,—length.

V. A geometrical surface or plane has theoretically

only two dimensions, namely, length and breadth.

VI. A geometrical body occupies space and has three

dimensions,—length, breadth and depth.

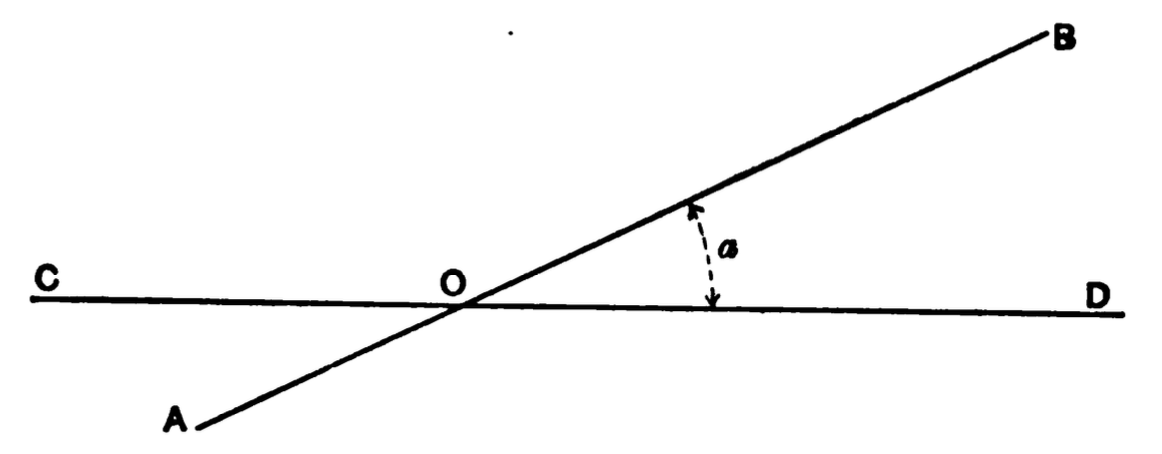

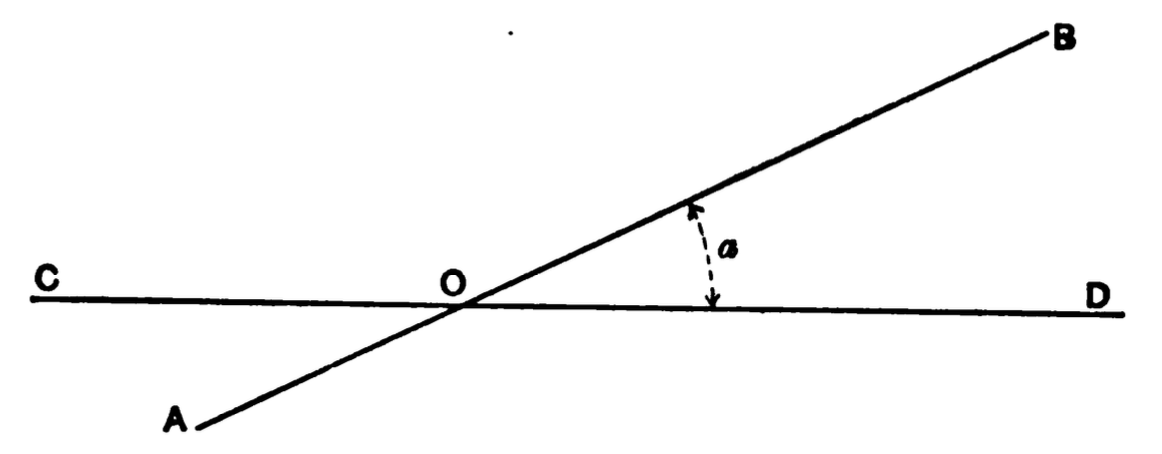

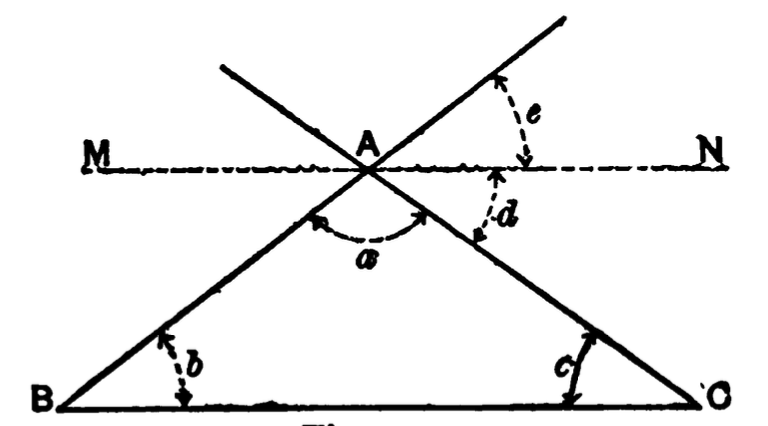

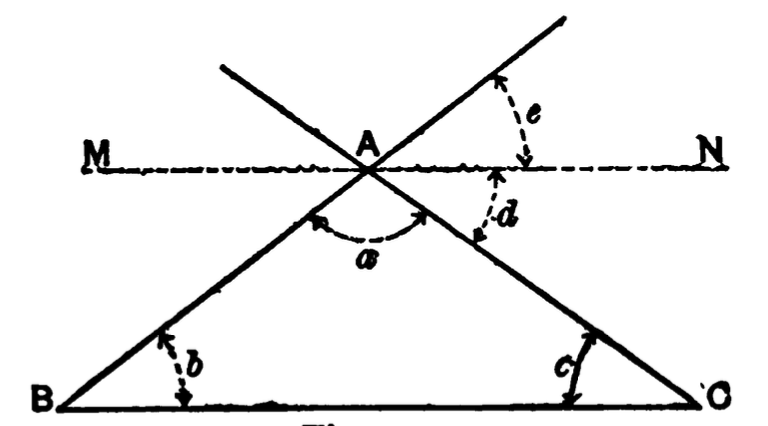

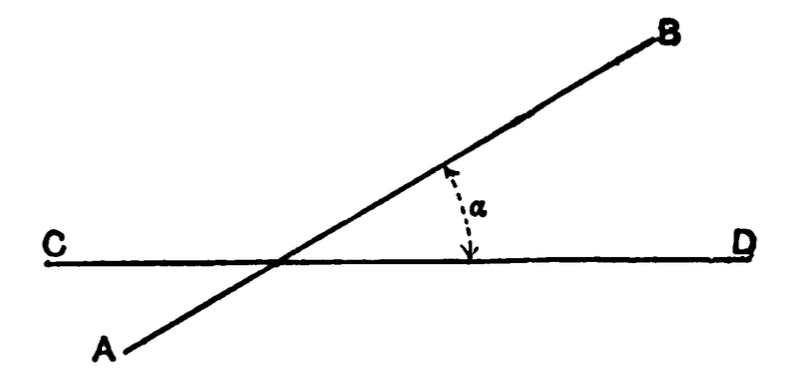

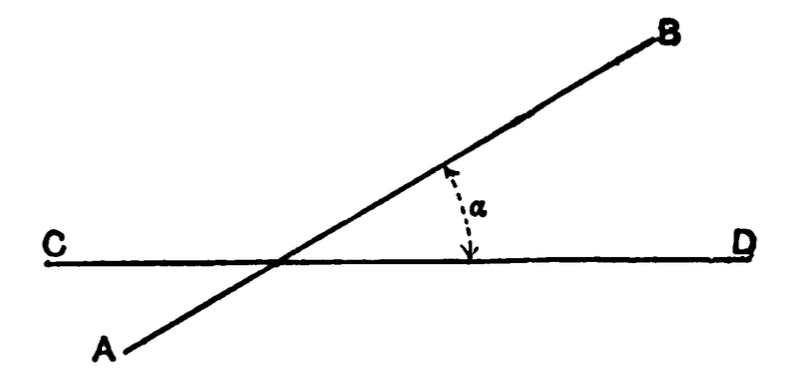

VI. An angle is the opening or divergence between

two straight lines which cut or intersect each other;

thus, in Fig. 1,

Fig. 1

062

Fig. 1

VIII. When two lines lying in the same surface or

plane are so drawn that they never approach or retreat

from each other, no matter how long they are actually

extended, they are said to be parallel; thus, in Fig. 2,

Fig. 2

the lines

Fig. 2

IX. A definite portion of a surface or plane bounded

by lines is called a polygon; thus, Fig. 3 shows a polygon.

Fig. 3

Fig. 3

063

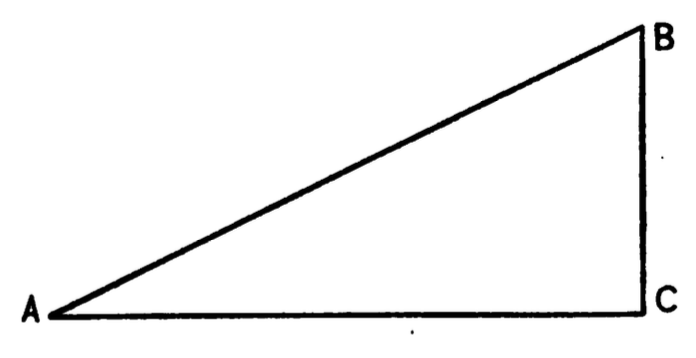

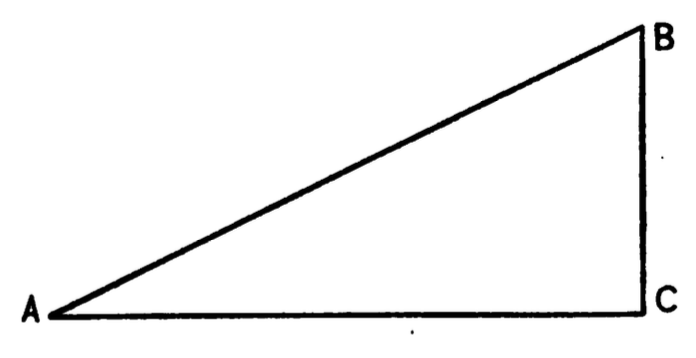

X. A polygon bounded by three sides is called a

triangle (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4

Fig. 4

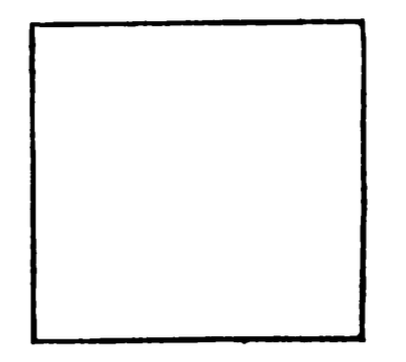

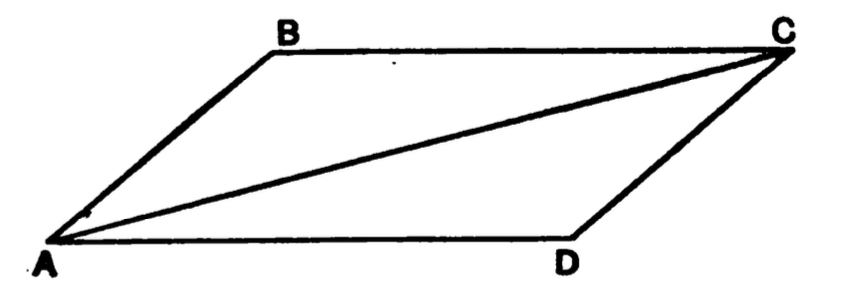

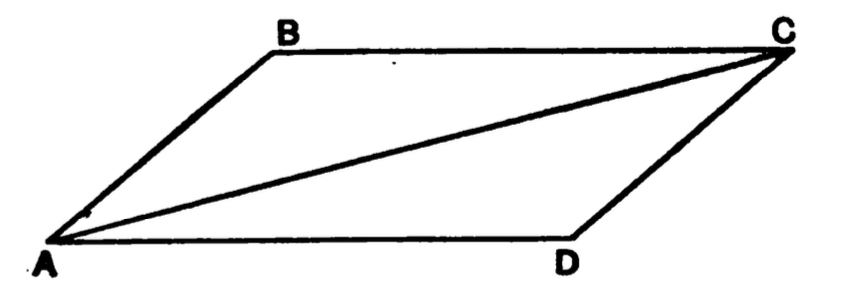

XI. A polygon bounded by four sides is called a

quadrangle (Fig. 5), and if the opposite sides are parallel,

a parallelogram (Fig. 6).

Fig. 5

Fig. 6

Fig. 5

Fig. 6

XII. When a line has revolved about a point until it

has swept through a complete circle, or 360°, it

comes back to its original

position. When it has revolved one quarter of a

circle, or 90°, away from its

original position, it is said

to be at right angles or

perpendicular to its original

position; thus, the angle

Fig. 7

Fig. 7

064

between the lines

XIII. An angle less than a right angle is called an

acute angle.

XIV. An angle greater than a right angle is called an

obtuse angle.

XV. The addition of two right angles makes a straight

line.

XVI. Two angles which when placed side by side or

added together make a right angle, or 90°, are said to

be complements of each other; thus,

XVII. Two angles which when added together form

180°, or a straight line, are said to be supplements of

each other; thus,

XVIII. When one of the inside angles of a triangle is

a right angle, it is called a right-angle triangle (Fig. 8),

Fig. 8

Fig. 8

and the side AB opposite the right angle is called its

hypothenuse.

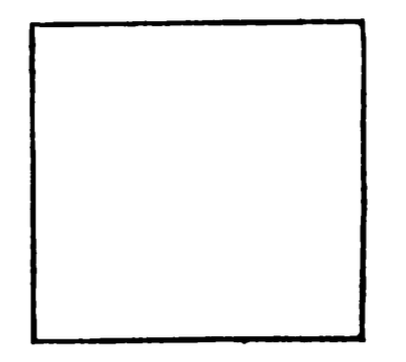

065

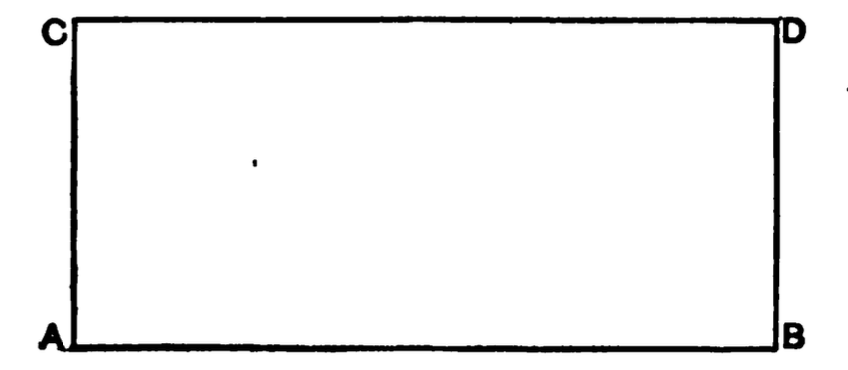

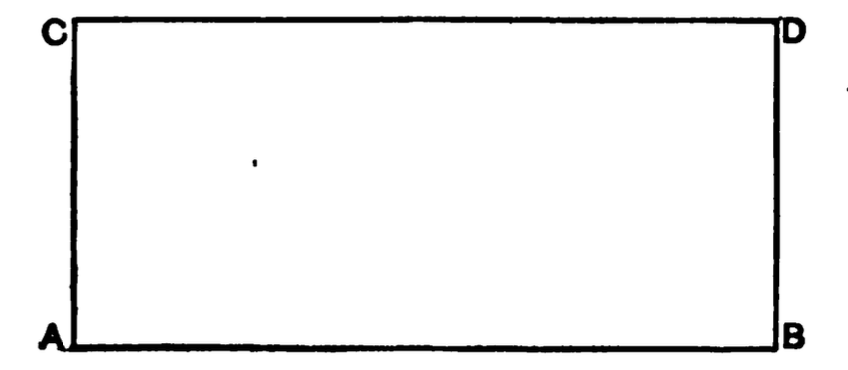

XIX. A rectangle is a parallelogram whose angles

are all right angles (Fig. 9a), and a square is a rectangle

whose sides are all equal (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9

Fig. 9a

Fig. 9

Fig. 9a

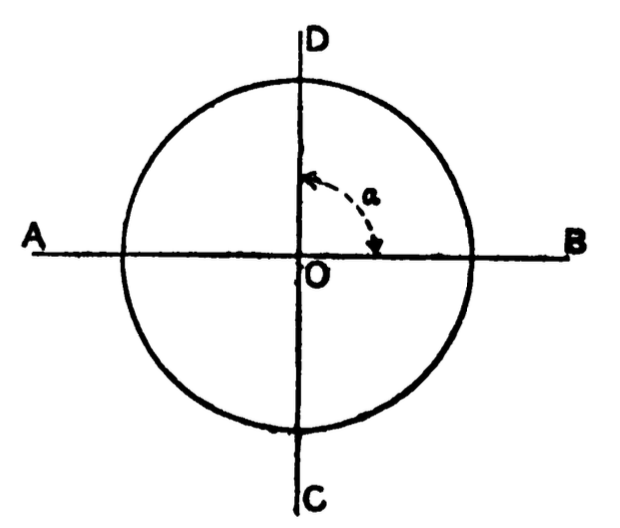

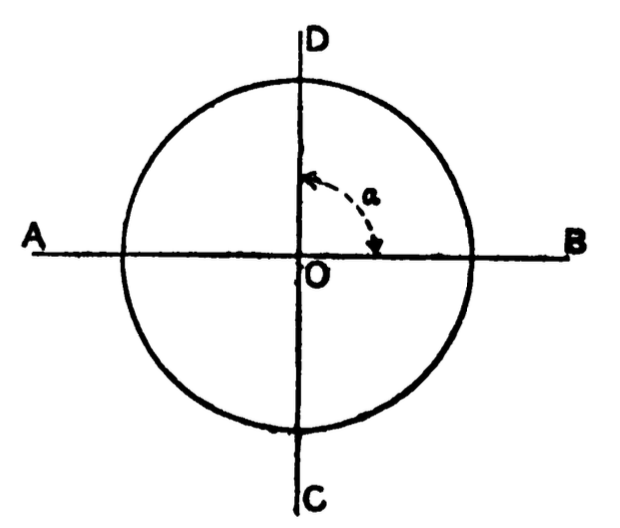

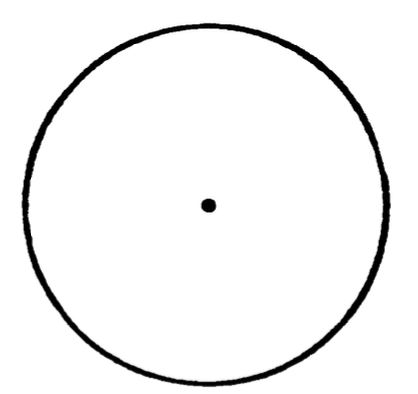

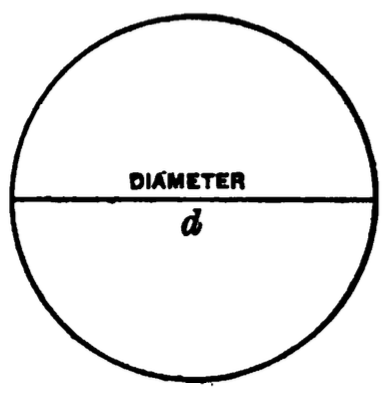

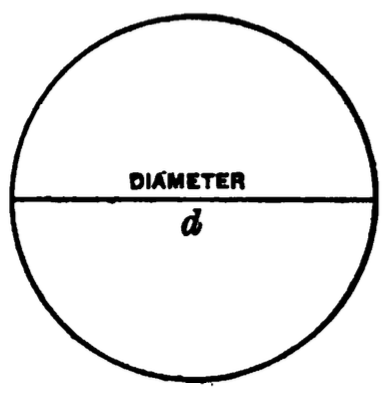

XX. A circle is a curved line, all points of which are

equally distant or equidistant from a fixed point called a

center (Fig. 10).

Fig. 10

Fig. 11

Fig. 10

Fig. 11

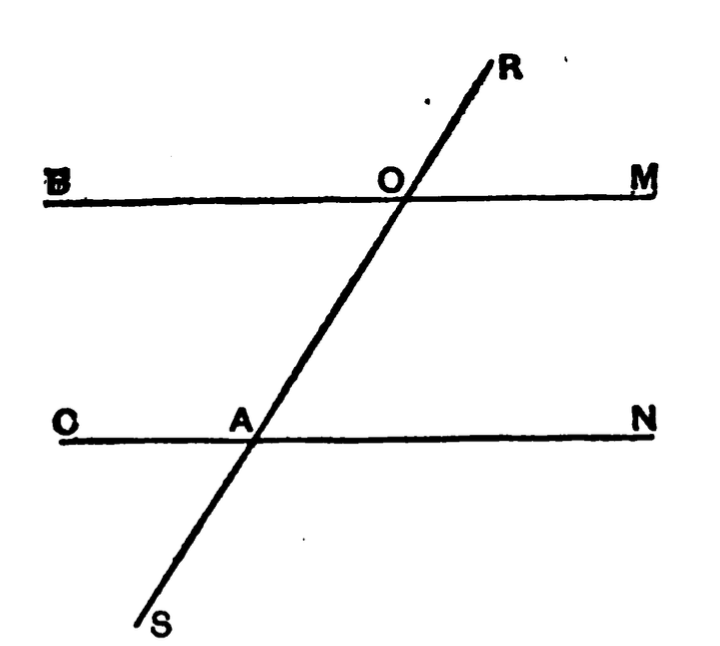

With these assumptions we may now proceed. Let us look at Fig. 11.

066

In general, we have this rule: When the corresponding

sides of any two angles are parallel to each other, the angles

are either equal or supplementary.

Triangles. — Let us now investigate some of the properties

of the triangle

Fig. 12

draw a line,

Fig. 12

But

067

This demonstration proves the fact that the sum of

all the inside or interior angles of any triangle is equal

to 180°, or, what is the same thing, two right angles.

Now, if the triangle is a right triangle and one of its

angles is itself a right angle, then the sum of the two

remaining angles must be equal to one right angle, or 90°.

This fact should be most carefully noted, as it is very

important.

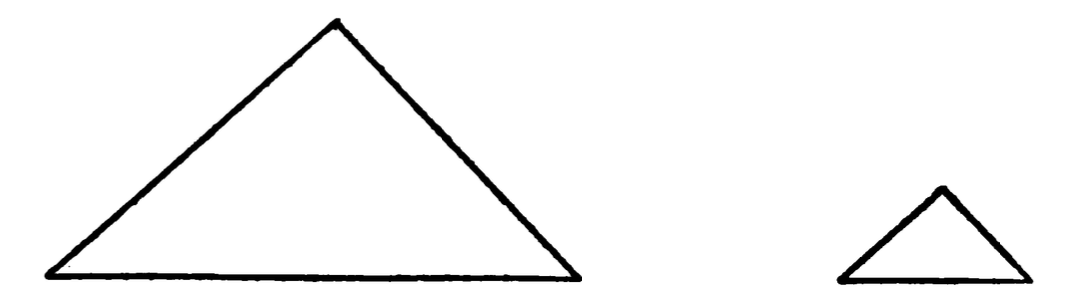

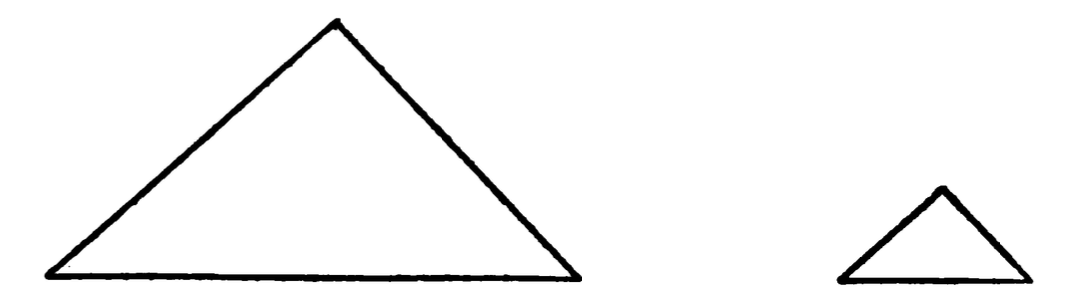

When we have two triangles with all the angles of

the one equal to the corresponding angles of the other,

as in Fig. 13, they are called similar triangles.

Fig. 13

Fig. 13

When we have two triangles with all three sides of

the one equal to the corresponding sides of the other,

they are equal to each other (Fig. 14), for they may be

Fig. 14

perfectly superposed on each other. In fact, the two

triangles are seen to be equal if two sides and the included

Fig. 14

068

angle of the one are equal to two sides and the

included angle of the other; or, if one side and two

angles of the one are equal to one side and the corresponding

angles respectively of the other; or, if one side

and the angle opposite to it of the one are equal to one

side and the corresponding angle of the other.

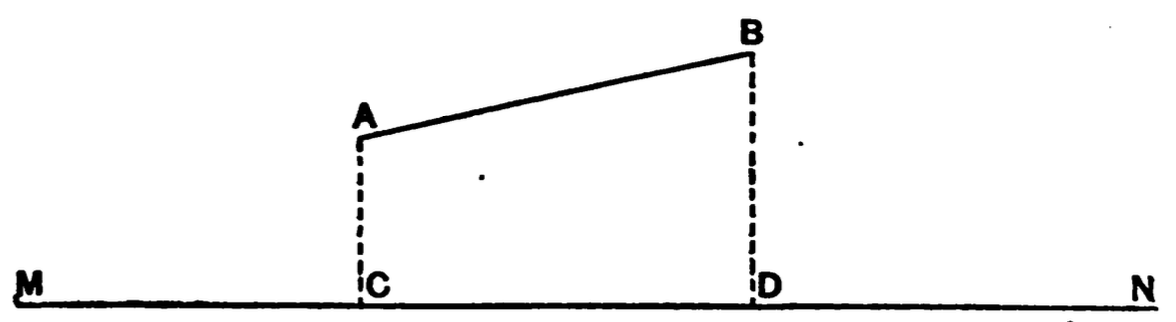

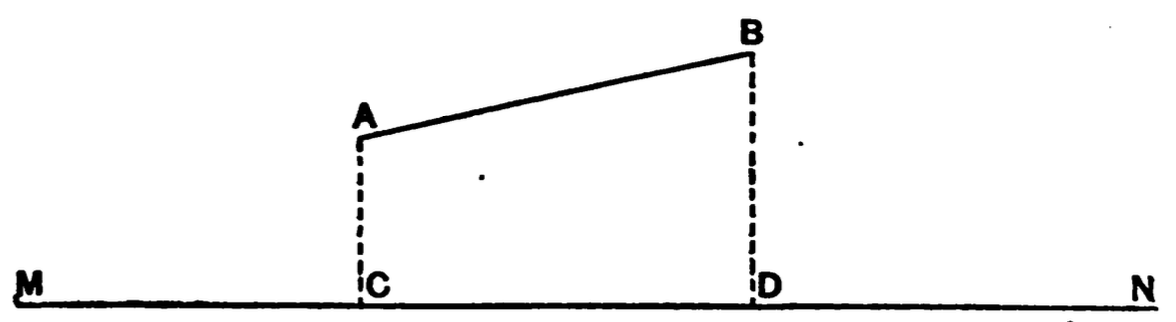

Projections. — The projection of any given tract, such

as

Fig. 15

Fig. 15

Rectangles and Parallelograms. — A line drawn between

opposite corners of a parallelogram is called a

diagonal; thus,

Fig. 16

Fig. 16

this diagonal that a body would move if pulled in the

direction of

Fig. 17

069

magnitudes as the relative lengths of Fig. 17

The area of a rectangle is equal to the product of the

length by the breadth; thus, in Fig. 17,

Area of.

This fact is so patent as not to need explanation.

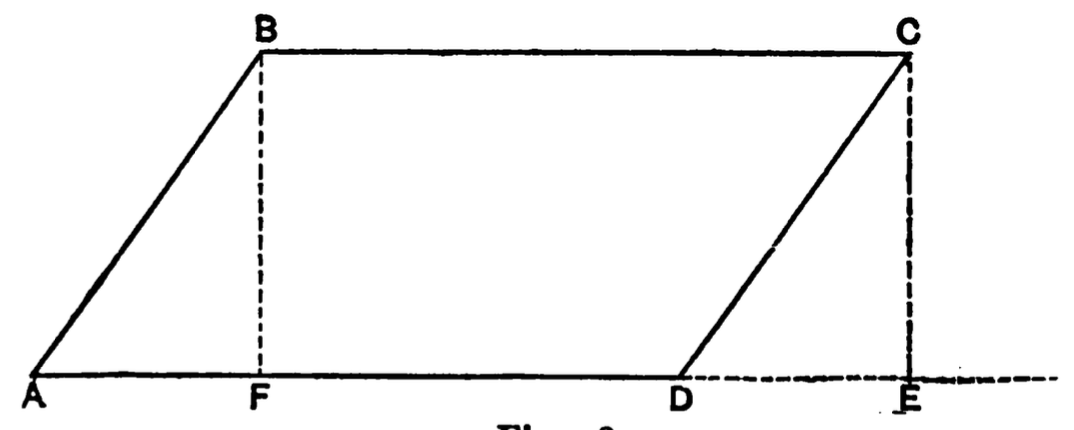

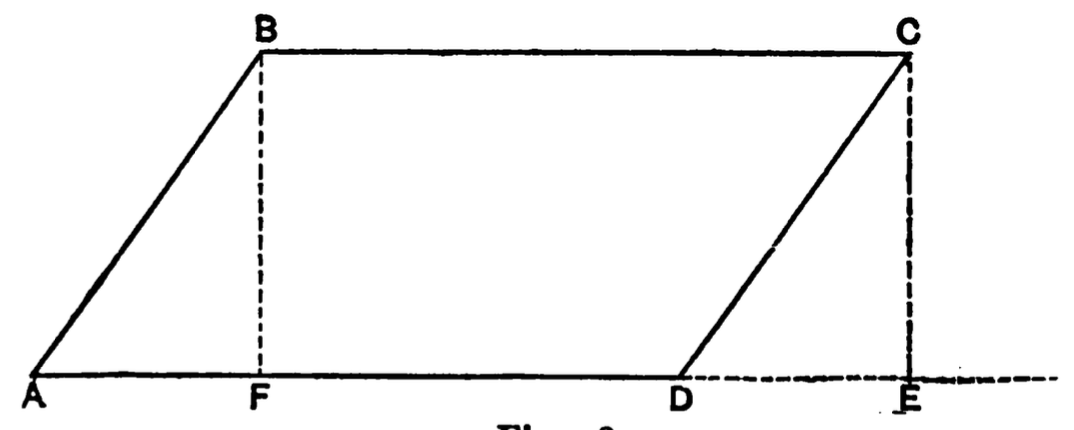

Suppose we have a parallelogram (Fig. 18), however,

what is its area equal to?

Fig. 18

Fig. 18

The perpendicular distance

070

Now we have the rectangle

Area of parallelogram

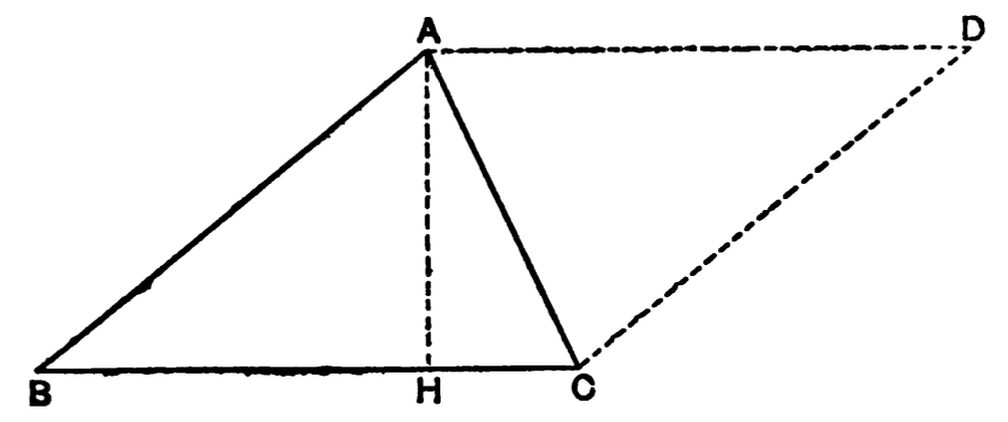

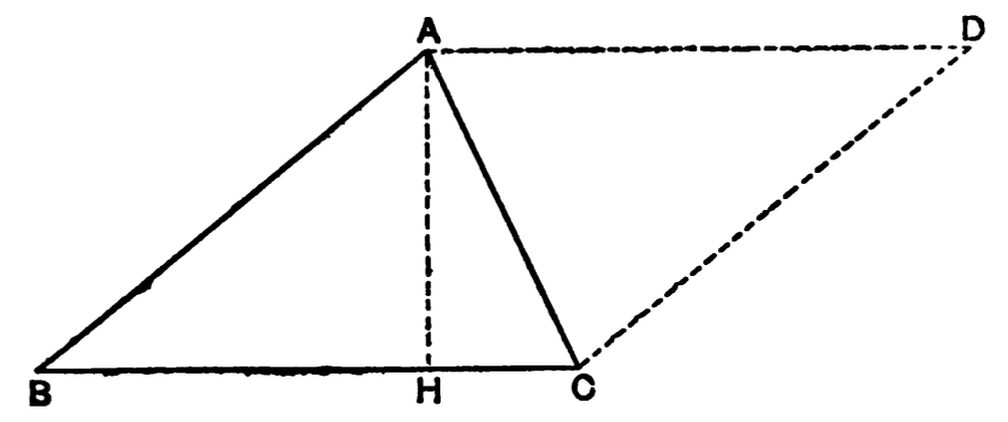

If, now, we consider the area of the triangle

Fig. 19

parallel to

Fig. 19

Area of the triangle

which means that the area of a triangle is equal to

one-half of the product of the base by the altitude.

071

Circles. — Comparison between the lengths of the

diameter and circumference of a circle (Fig. 20) made

Fig. 20

with the utmost care shows that

the circumference is 3.1416 times as

long as the diameter. This constant,

3.1416, is usually expressed

by the Greek letter pi (

Fig. 20

circum. =

circum. =

if

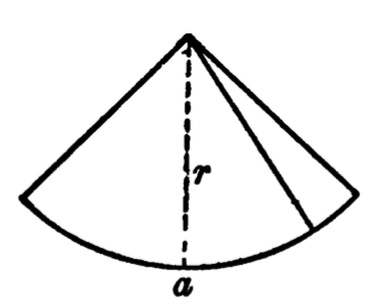

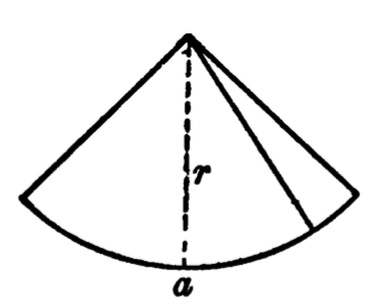

The area of a segment of a circle (Fig. 21), like the

area of a triangle, is equal to

Fig. 21

Fig. 21

base by the altitude, or

,

Area circle.

072

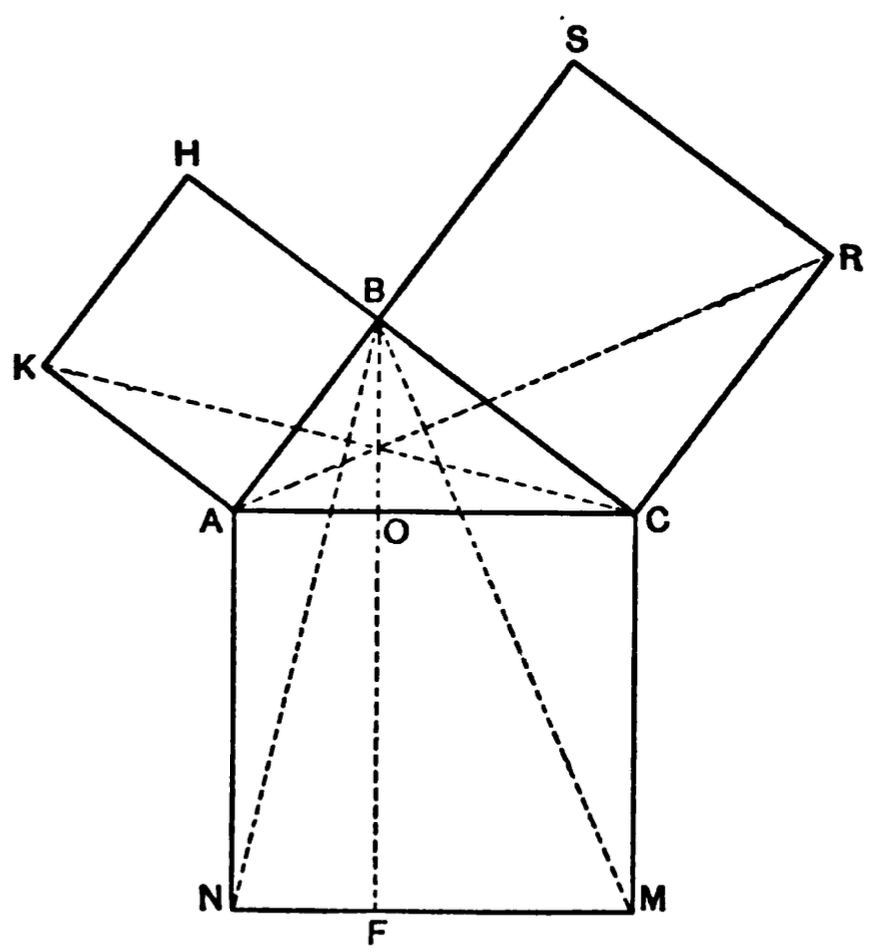

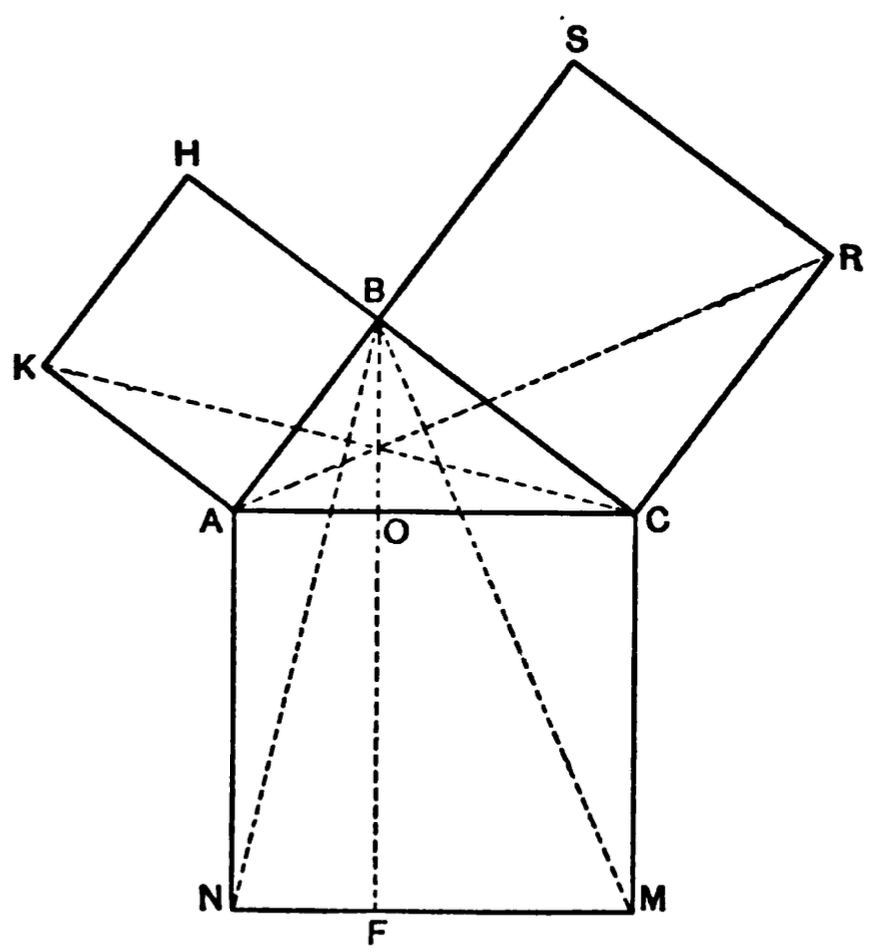

I will conclude this chapter by a discussion of one of

the most important properties of the right-angle triangle,

namely, that the square erected on its hypothenuse

is equal to the sum of the squares erected on

its other two sides; that is, that in the triangle

Fig. 22

Fig. 22

To prove

,

or

length= length + length .

This is a difficult problem and one of the most interesting

and historic ones that the whole realm of mathematics

can offer, therefore I will only suggest its solution

073

and leave a little reasoning for the student himself

to do.

triangle= triangle BMC,

triangle=

=of the square ,

triangle=

=of rectangle .

Therefore

of square = of rectangle ,

or

.

Similarly for the other side

.

But

= whole square .

Therefore

.

.

PROBLEMS

1. What is the area of a rectangle 8 ft. long by 12 ft. wide?

2. What is the area of a triangle whose base is 20 ft. and whose altitude is 18 ft.?

3. What is the area of a circle whose radius is 9 ft.?

4. What is the length of the hypothenuse of a right-angle triangle if the other two sides are respectively 6 ft. and 9 ft.?

074

5. What is the circumference of a circle whose diameter is 20 ft.?

6. The hypothenuse of a right-angle triangle is 25 ft. and one side is 18 ft.; what is the other side?

7. If the area of a circle is 600 sq. ft., what is its diameter?

8. The circumference of the earth is 25,000 miles; what is its diameter in miles?

9. The area of a triangle is 30 sq. ft. and its base is 8 ft.; what is its altitude?

10. The area of a parallelogram is 100 sq. feet and its base is 25 ft.; what is its altitude?

075

CHAPTER XI

Elementary Principles of Trigonometry

TRIGONOMETRY is the science of angles; its province is

to teach us how to measure and employ angles with the

same ease that we handle lengths and areas.

In a previous chapter we have defined an angle as the

opening or the divergence between two intersecting

lines,

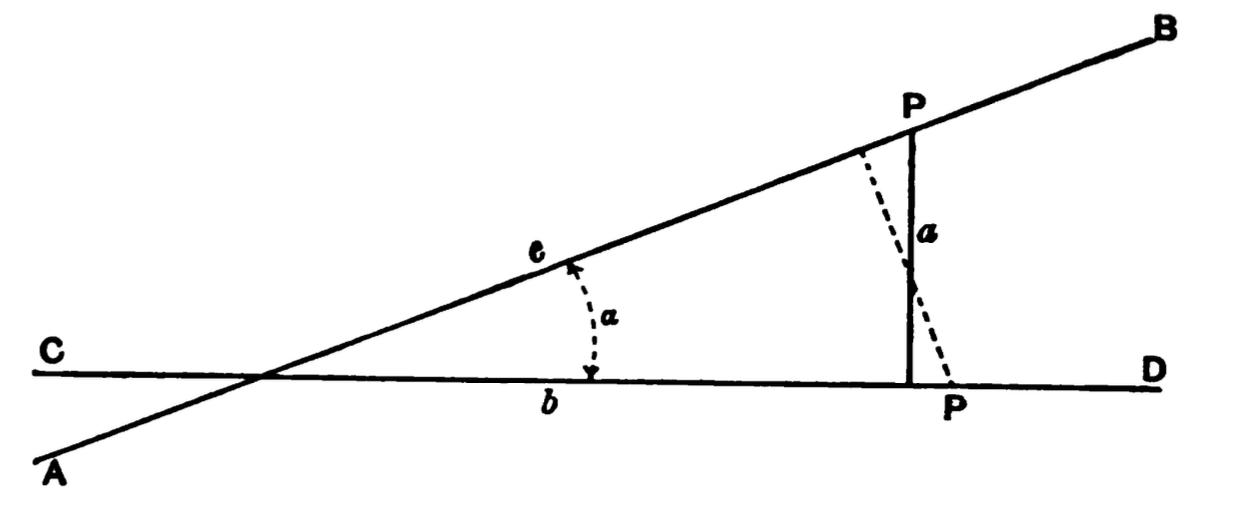

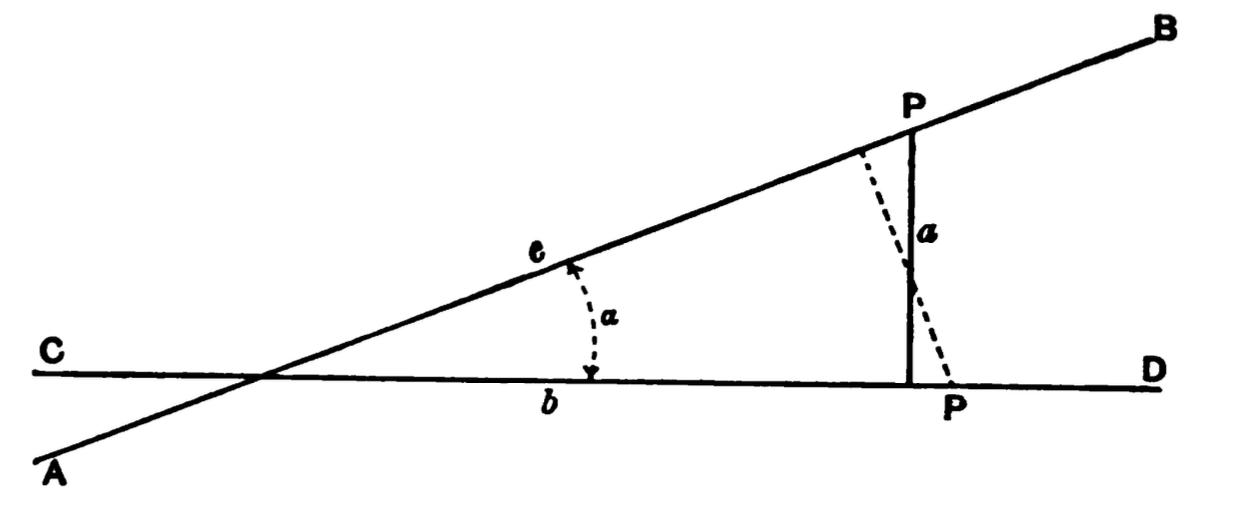

Fig. 23

are we going to measure this angle? We have already

seen that we can do this in one way by employing

degrees, a complete circle being 360°. But there are

many instances which the student will meet later on

where the use of degrees would be meaningless. It

is then that certain constants connected with the angle,

called its functions, must be resorted to. Suppose we

have the angle

Fig. 24

Fig. 23

076

a point anywhere either on the line Fig. 24

be perpendicular to

sine,

cosine,

tangent,

which means that the sine of an angle is obtained by

dividing the side opposite to it by the hypothenuse; the

cosine, by dividing the side adjacent to it by the hypothenuse;

and the tangent, by dividing the side opposite

by the side adjacent.

These values, sine, cosine and tangent, are therefore

nothing but ratios,—pure numbers,—and under no circumstances

077

should be taken for anything else. This is

one of the greatest faults that I have to find with many

texts and handbooks in not insisting on this point.

Looking at Fig. 24, it is evident that no matter where

I choose

Likewise

Since these functions, namely, sine, cosine and tangent,

of any angle remain the same at all times, they

become very convenient handles for employing the

angle. The sines, cosines and tangents of all angles of

every size may be actually measured and computed

with great care once and for all time, and then arranged

in tabulated form, so that by referring to this table one

can immediately find the sine, cosine or tangent of any

angle; or, on the other hand, if a certain value said to

078

be the sine, cosine or tangent of an unknown angle is

given, the angle that it corresponds to may be found

from the table. Such a table may be found at the end

of this book, giving the sines, cosines and tangents of

all angles taken 6 minutes apart. Some special compilations

of these tables give the values for all angles taken

only one minute apart, and some even closer, say 10 seconds

apart.

On reference to the table, the sine of 10° is .1736, the

cosine of 10° is .9848, the sine of 24° 36' is .4163, the cosine

of 24° 36' is .9092. In the table of sines and cosines

the decimal point is understood to be before every value,

for, if we refer back to our definition of sine and cosine,

we will see that these values can never be greater than

1; in fact, they will always be less than 1, since the

hypothenuse

079

Now let us work backwards. Suppose we are given .3437

as the sine of a certain angle, to find the angle.

On reference to the table we find that this is the sine

of 20° 6', therefore this is the angle sought. Again,

suppose we have .8878 as the cosine of an angle, to find

the angle. On reference to the table we find that this

is the angle 27° 24'. Likewise suppose we are given

3.5339 as the tangent of an angle, to find the angle.

The tables show that this is the angle 74° 12'.

When an angle or value which is sought cannot be

found in the tables, we must prorate between the next

higher and lower values. This process is called interpolation,

and is merely a question of proportion. It will

be explained in detail in the chapter on Logarithms.

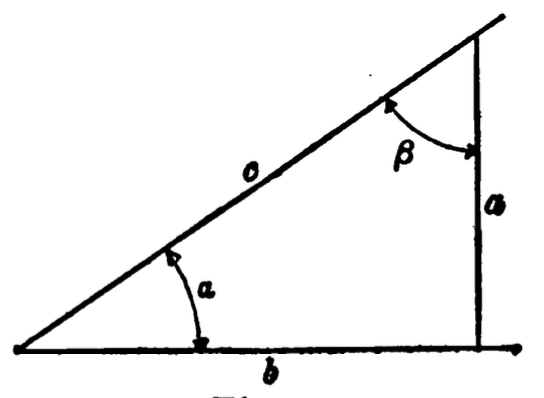

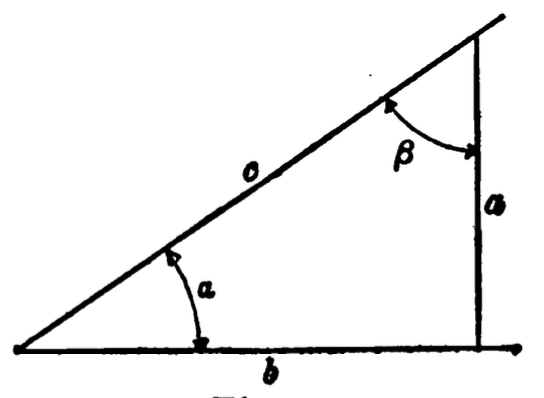

Relation of Sine and Cosine. — On reference to Fig.

Fig. 25

25 we see that the sine

Fig. 25

Remembering, always the fundamental definition

of sine and cosine, namely,

sine =,

cosine =,

080

we see that the cosine sine= cosine .

Now, if we refer back to our geometry, we will remember

that the sum of the three angles of a triangle

= 180°, or two right angles, and therefore in a right-angle

triangle

Other Functions. — There are some other functions

of the angle which are seldom used, but which I will

mention here, namely,

Cotangent =,

Secant =,

Cosecant =.

Other Relations of Sine and Cosine. — We have seen

081

that the sine (1)

Dividing equation (1) by

+ = 1

But this is nothing but the square of the sine plus the

square of the cosine of

sine cosine .

Other relations whose proof is too intricate to enter

into now are

sine,

cos,

or cos.

Use of Trigonometry. — Trigonometry is invaluable

in triangulation of all kinds. When two sides or one

side and an acute angle of a right-angle triangle are

Fig. 26

Fig. 26

given, the other two sides can be easily found. Suppose

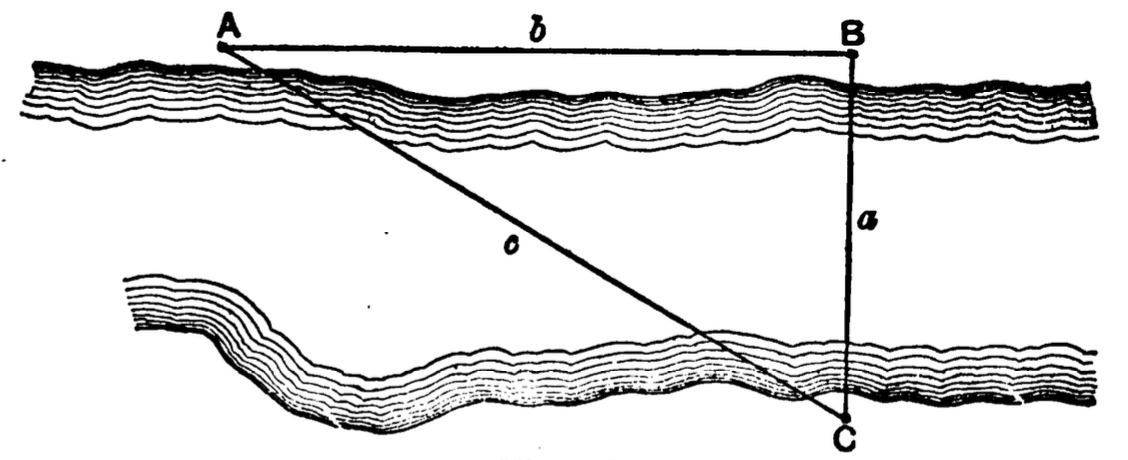

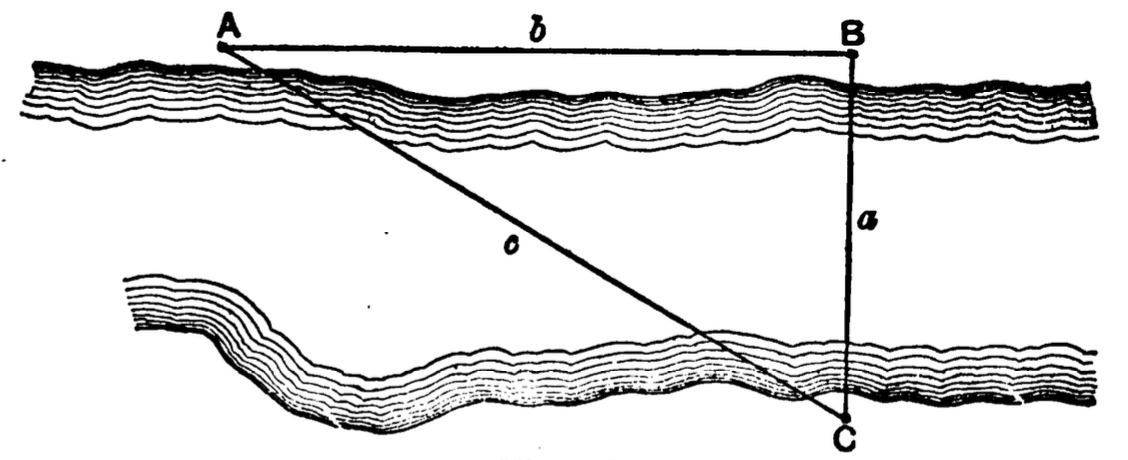

we wish to measure the distance

082

and measure the distance .

Suppose

.

The tables show that the tangent of 40° is .8391;

then

therefore

Thus we have found the distance across the river to be

839.1 ft.

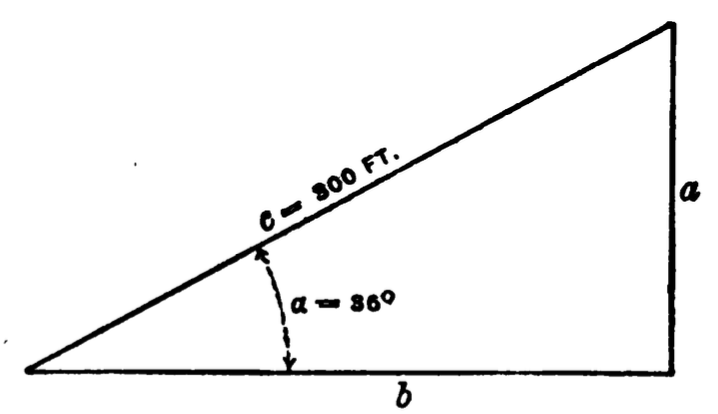

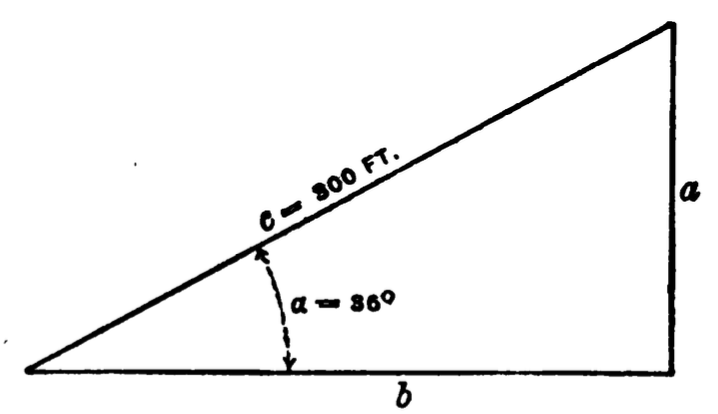

Fig. 27

Fig. 27

Likewise in Fig. 27, suppose

,

or

.

083

From the tables

or,

.

Likewise

.

From table,

,

therefore

,

or

.

Now, if we had been told that

.

Therefore

,

ft.

The tables show that this corresponds to the angle

Therefore

.

Now to find

,

.

084

From tables,

,

or

.

And thus we may proceed, the use of a little judgment

being all that is necessary to the solution of the most

difficult problems of triangulation.

PROBLEMS

1. Find the sine, cosine and tangent of 32° 20'.

2. Find the sine, cosine and tangent of 81° 24'.

3. What angle is it whose sine is .4320?

4. What angle is it whose cosine is .1836?

5. What angle is it whose tangent is .753?

6. What angle is it whose cosine is .8755?

In a right-angle triangle—

7. If= 300 ft. and = 30°, what are and ?

8. If= 500 ft. and = 315 ft., what are and ?

9. If= 1250 ft. and = 80°, what are and ?

I HAVE inserted this chapter on logarithms because

I consider a knowledge of them very essential to the

education of any engineer.

Definition. — A logarithm is the power to which we

must raise a given base to produce a given number.

Thus, suppose we choose 10 as our base, we will say

that 2 is the logarithm of 100, because we must raise 10 to

the second power—in other words, square it—in order

to produce 100. Likewise 3 is the logarithm of 1000,

for we have to raise 10 to the third power (thus,

The base of the universally used Common System of

logarithms is 10; of the Napierian or Natural System,

We see that the logarithms of such numbers as 100,

1000, 10,000, etc., are easily detected; but suppose we

have a number such as 300, then the difficulty of finding

its logarithm is apparent. We have seen that

086

namely 2 and 3 respectively. Reference to a table of

logarithms at the end of this book, which we will explain

later, shows that the logarithm of 300 is 2.4771,

which means that 10 raised to the 2.4771ths power will

give 300. The whole number in a logarithm, for example

the 2 in the above case, is called the characteristic;

the decimal part of the logarithm, namely, 4771, is

called the mantissa. It will be hard for the student to

understand at first what is meant by raising 10 to a

fractional part of a power, but he should not worry

about this at the present time; as he studies more

deeply into mathematics the notion will dawn on him

more clearly.

We now see that every number has a logarithm, no

matter how large or how small it may be; every number

can be produced by raising 10 to some power, and this

power is what we call the logarithm of the number.

Mathematicians have carefully worked out and tabulated

the logarithm of every number, and by reference

to these tables we can find the logarithm corresponding

to any number, or vice versa. A short table of logarithms

is shown at the end of this book.

Now take the number 351.1400; we find its logarithm

is 2.545,479. Like all numbers which lie between 100

and 1000 its characteristic is 2. The numbers which

lie between 1000 and 10,000 have 3 as a characteristic;

between 10 and 100, 1 as a characteristic. We therefore

087

have the rule that the characteristic is always one

less than the number of places to the left of the decimal

point. Thus, if we have the number 31875.12, we

immediately see that the characteristic of its logarithm

will be 4, because there are five places to the left of the

decimal point. Since it is so easy to detect the characteristic,

it is never put in logarithmic tables, the mantissa

or decimal part being the only part that the tables

need include.

If one looked in a table for a logarithm of 125.60, he

would only find .09,899. This is only the mantissa of

the logarithm, and he would himself have to insert the

characteristic, which, being one less than the number of

places to the left of the decimal point, would in this

case be 2; therefore the logarithm of 125.6 is 2.09,899.

Furthermore, the mantissæ of the logarithms of

3.4546, 34.546, 345.46, 3454.6, etc., are all exactly the

same. The characteristic of the logarithm is the only

thing which the decimal point changes, thus:

log 3.4546 = 0.538,398,

log 34.546 = 1.538,398,

log 345.46 = 2.538,398,

log 3454.6 = 3.538,398,

etc.

Therefore, in looking for the logarithm of a number,

first put down the characteristic on the basis of the

088

above rules, then look for the mantissa in a table,

neglecting the position of the decimal point altogether.

Thus, if we are looking for the logarithm of .9840, we

first write down the characteristic, which in this case

would be −1 (there are no places to the left of the

decimal point in this case, therefore one less than none

is −1). Now look in a table of logarithms for the

mantissa which corresponds to .9840, and we find this

to be .993,083; therefore

log .9840 = −1.993,083.

If the number had been 98.40 the logarithm would have

been +1.993,083.

When we have such a number as .084, the characteristic

of its logarithm would be −2, there being one

less than no places at all to the left of its decimal point;

for, even if the decimal point were moved to the right

one place, you would still have no places to the left of

the decimal point; therefore

log .00,386 = −3.586,587,

log 38.6 = 1.586,587,

log 386 = 2.586,587,

log 386,000 = 5.586,587.

Interpolation. — Suppose we are asked to find the

logarithm of 2468; immediately write down 3 as the

characteristic. Now, on reference to the logarithmic

089

table at the end of this book, we see that the logarithms

of 2460 and 2470 are given, but not 2468. Thus:

log 2460 = 3.3909,

log 2468 = ?

log 2470 = 3.3927.

We find that the total difference between the two

given logarithms, namely 3909 and 3927, is 16, the

total difference between the numbers corresponding to

these logarithms is 10, the difference between 2460 and

2468 is 8; therefore the logarithm to be found lies

log of 2468 = 3.39,218.

Reference to column 8 in the interpolation columns to the

right of the table would have given this value at once.

Many elaborate tables of logarithms may be purchased

at small cost which make interpolation almost unnecessary

for practical purposes.

Now let us work backwards and find the number if

we know its logarithm. Suppose we have given the

logarithm 3.6201. Referring to our table, we see that

the mantissa .6201 corresponds to the number 417; the

characteristic 3 tells us that there must be four places

to the left of the decimal point; therefore

3.6201 is the log of 4170.0.

090

Now, for interpolation we have the same principles

aforesaid. Let us find the number whose log is −3.7304.

In the table we find that

log 7300 corresponds to the number 5370,

log 7304 corresponds to the number ?

log 7308 corresponds to the number 5380.

Therefore it is evident that

7304 corresponds to 5375.

Now the characteristic of our logarithm is −3; from

this we know that there must be two zeros to the left

of the decimal point; therefore

−3.7304 is the log of the number .005375.

Likewise

−2.7304 is the log of the number .05375,

−7304 is the log of the number 5.375,

4.7304 is the log of the number 53,750.

Use of the Logarithm. — Having thoroughly understood

the nature and meaning of a logarithm, let us

investigate its use mathematically. It changes multiplication

and division into addition and subtraction; involution

and evolution into multiplication and division.

We have seen in algebra that

and that, or ,

, or .

091

In other words, multiplication or division of like symbols

was accomplished by adding or subtracting their exponents,

as the case may be. Again, we have seen that

or,

.

In the first case

log of,

log of.

Then

But.

We have simply added the exponents, remembering that

these exponents are nothing but the logarithms of 336

and 5380 respectively.

Well, now, what number is

1,808,000.

If the student notes carefully the foregoing he will see

that in order to multiply 336 by 5380 we simply find

092

their logarithms, add them together, getting another

logarithm, and then find the number corresponding

to this logarithm. Any numbers may be multiplied

together in this simple manner; thus, if we multiply

log 217 = 2.3365

log 4876 = 3.6880

log 3.185 = .5031

log .0438 = −2.6415 [*]

log 890 = 2.9494

------

Adding we get

8.1185

[*] The −2 does not carry its negativity to the mantissa.

We must now find the number corresponding to the

logarithm 8.1185. Our tables show us that

8.1185 is the log of 131,380,000.

Therefore 131,380,000 is the result of the above multiplication.

To divide one number by another we subtract the

logarithm of the latter from the logarithm of the

former; thus,

log 3865 = 3.5872

log 735 = 2.8663

______

.7209

The tables show that .7209 is the logarithm of 5.259;

therefore

.

093

As explained above, if we wish to square a number, we

simply multiply its logarithm by 2 and then find what

number the result is the logarithm of. If we had

wished to raise it to the third, fourth or higher power,

we would simply have multiplied by 3, 4 or higher power,

as the case may be. Thus, suppose we wish to cube

9879; we have

log 9897 = 3.9947

3

_____

11.9841

11.9841 is the log of 964,000,000,000;

therefore 9879 cubed = 964,000,000,000.

Likewise, if we wish to find the square root, the cube

root, or fourth root or any root of a number, we simply

divide its logarithm by 2, 3, 4 or whatever the root may

be; thus, suppose we wish to find the square root of

36,850, we have

log 36,850 = 4.5664.2.2832 is the log. of 191.98; therefore the square root of 36,850 is 191.98.

4.5664 ÷ 2 = 2.2832.

The student should go over this chapter very carefully,

so as to become thoroughly familiar with the

principles involved.

094

PROBLEMS

1. Find the logarithm of 3872.

2. Find the logarithm of 73.56.

3. Find the logarithm of .00988.

4. Find the logarithm of 41,267.

5. Find the number whose logarithm is 2.8236.

6. Find the number whose logarithm is 4.87175.

7. Find the number whose logarithm is −1.4385.

8. Find the number whose logarithm is −4.3821.

9. Find the number whose logarithm is 3.36175.

10. Multiply 2261 by 4335.

11. Multiply 6218 by 3998.

12. Multiply 231.9 by 478.8 by 7613 by .921.

13. Multiply .00983 by .0291.

14. Multiply .222 by .00054.

15. Divide 27,683 by 856.

16. Divide 4337 by 38.88.

17. Divide .9286 by 28.75.

18. Divide .0428 by 1.136.

19. Divide 3995 by .003,337.

20. Find the square of 4291.

21. Raise 22.91 to the fourth power.

22. Raise .0236 to the third power.

23. Find the square root of 302,060.

24. Find the cube root of 77.85.

25. Find the square root of .087,64.

26. Find the fifth root of 226,170,000.

095

CHAPTER XIII

Elementary Principles of Coördinate Geometry

COÖRDINATE Geometry may be called graphic algebra,

or equation drawing, in that it depicts algebraic equations

not by means of symbols and terms but by means

of curves and lines. Nothing is more familiar to the

engineer, or in fact to any one, than to see the results of

machine tests or statistics and data of any kind shown

graphically by means of curves. The same analogy

exists between an algebraic equation and the curve

which graphically represents it as between the verbal

description of a landscape and its actual photograph;

the photograph tells at a glance more than could be

said in many thousands of words. Therefore the student

will realize how important it is that he master the

few fundamental principles of coördinate geometry which

we will discuss briefly in this chapter.

An Equation. — When discussing equations we remember

that where we have an equation which contains

two unknown quantities, if we assign some numerical

value to one of them we may immediately find the corresponding

numerical value of the other; for example, take

the equation

.

096

In this equation we have two unknown quantities,

namely,

If, then ,

, ,

, ,

, ,

, , etc.

The equation then represents the relation in value

existing between

Now let us plot the corresponding values,

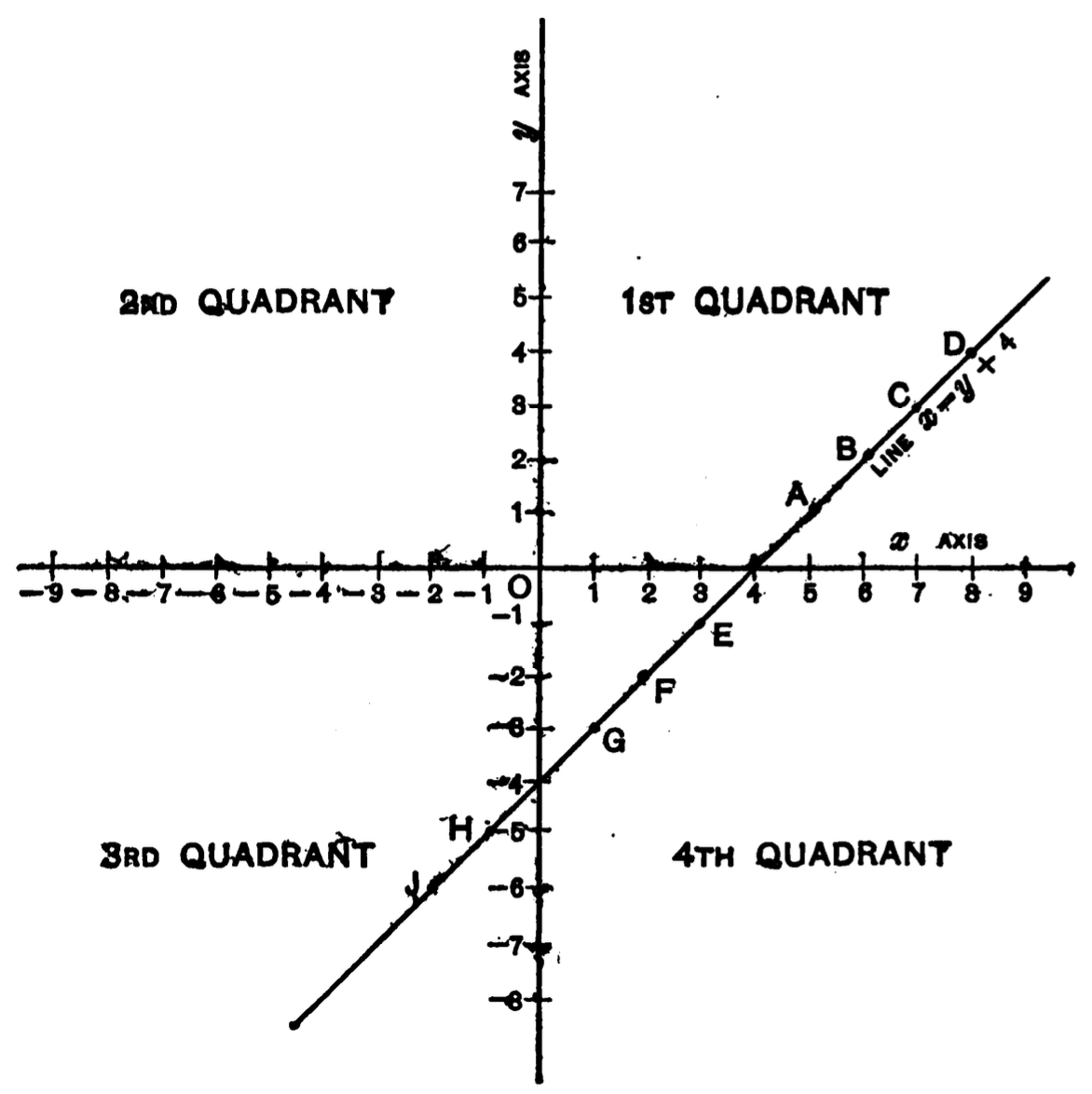

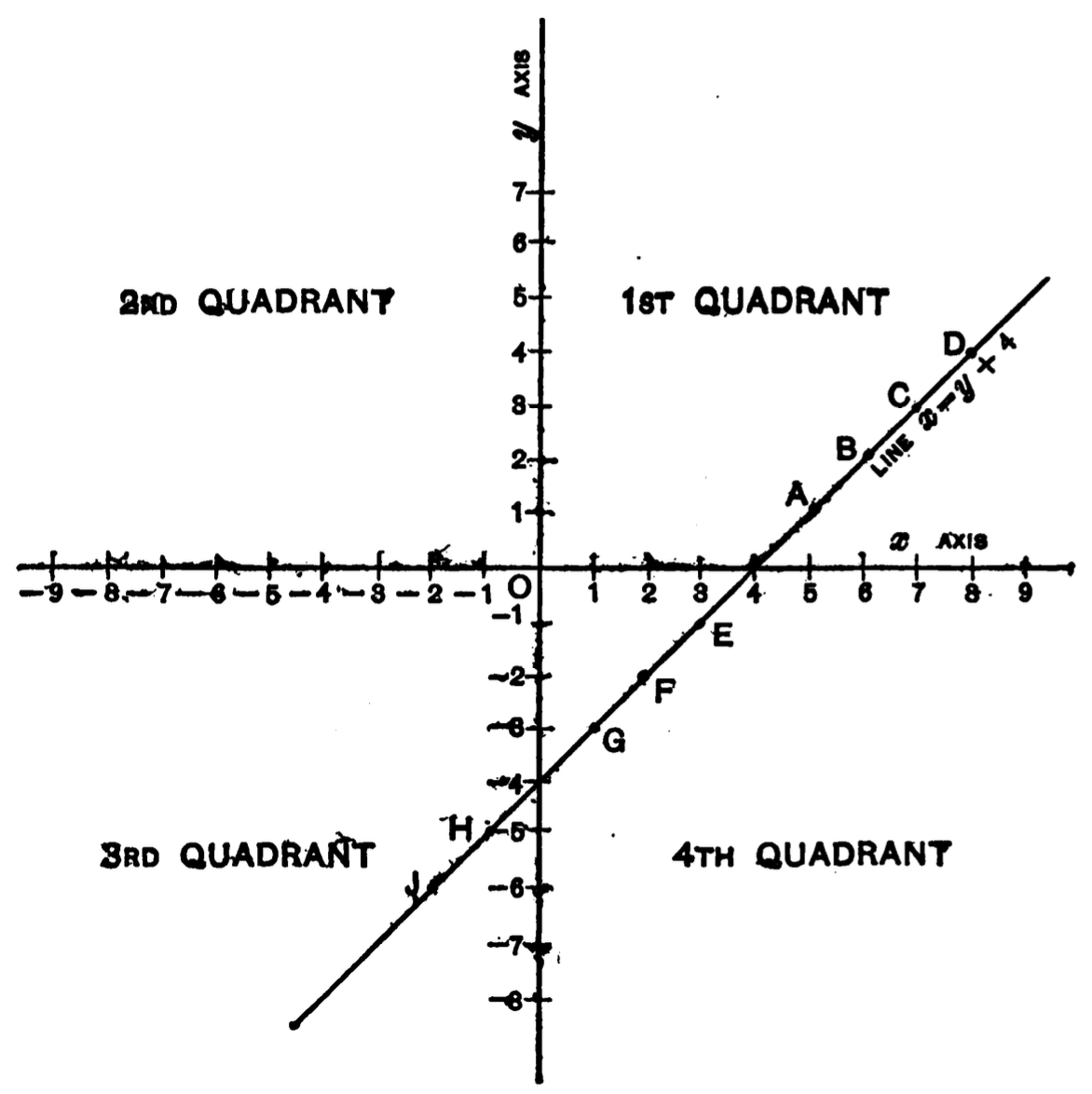

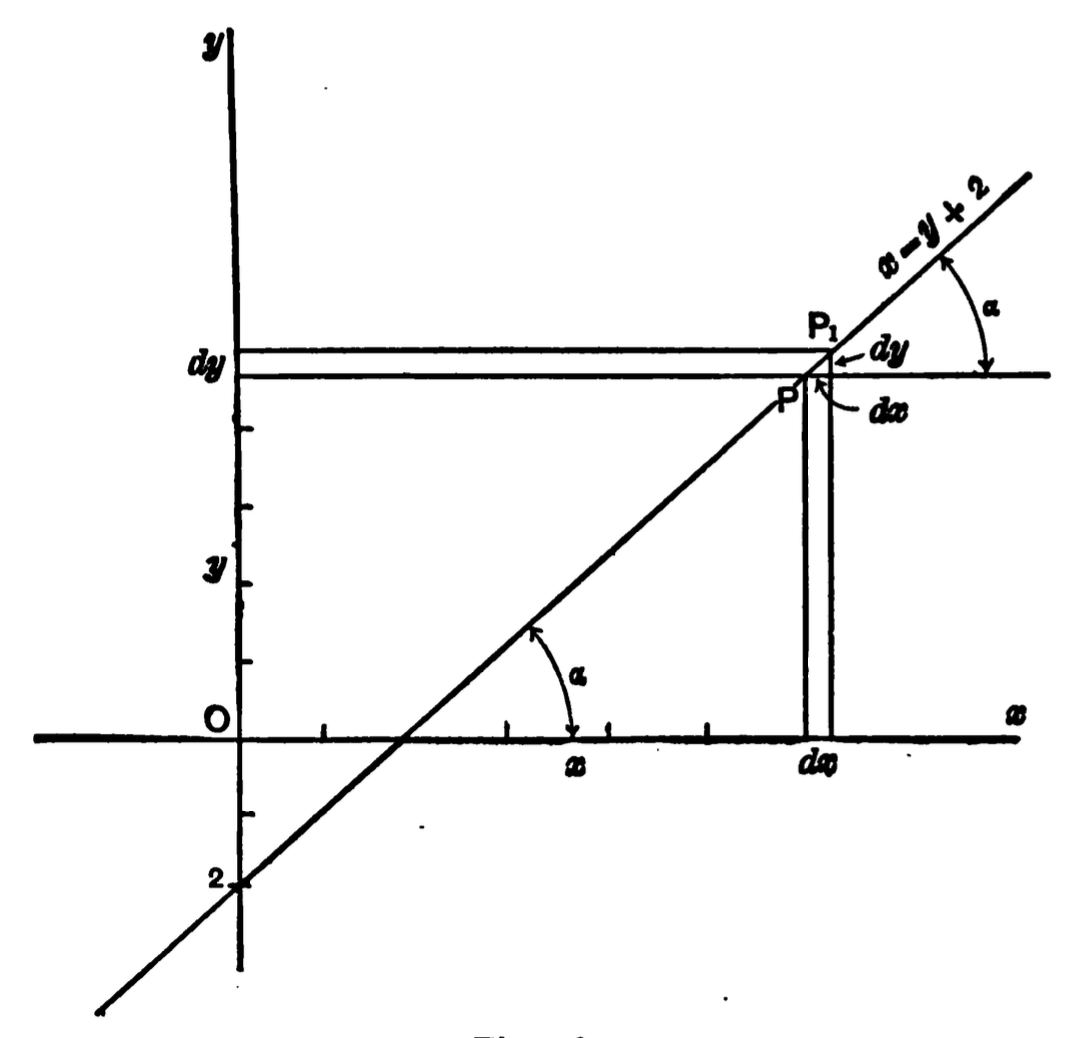

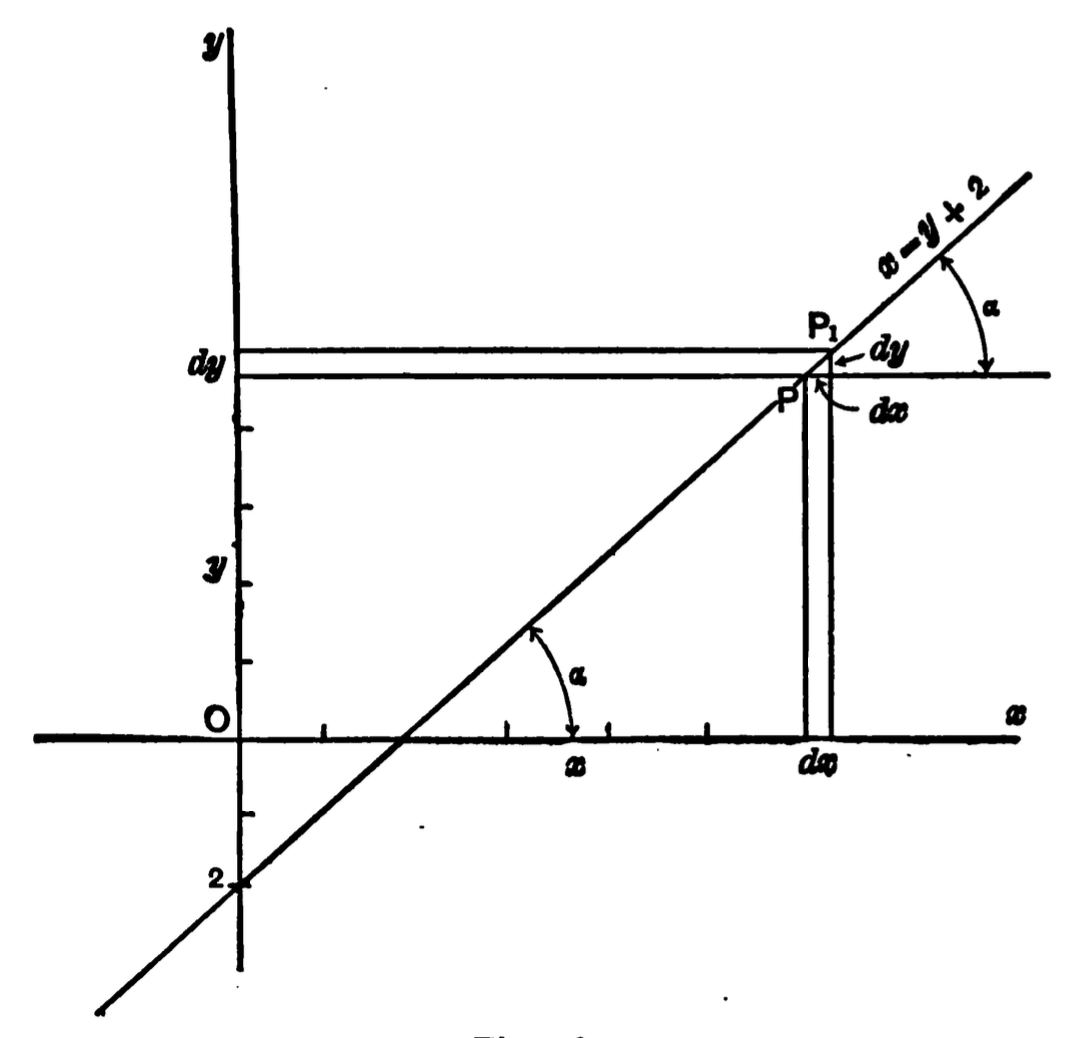

Fig. 28

097

gives us the point Fig. 28

way that the equation does algebraically. If this line

has been drawn accurately we can from it find out at

a glance what value of

098

we run our eyes along the x axis until we come to

Negative Values of x and y. — When we started at o

and counted 1, 2, 3, 4, etc., to the right along the x

axis, we might just as well have counted to the left,

−1, −2, −3, −4, etc. (Fig. 28), and likewise we

might have counted downwards along the y axis, −1,

−2, −3, −4, etc. The values, then, to the left of o

on the x axis and below o on the y axis are the negative

values of x and y. Still using the equation x = y + 4,

let us give the following values to y and note the corresponding

values of x in the equation x = y + 4:

If, then ,

, ,

, ,

, ,

, ,

, ,

, ,

, .

The point

099

The student will note that all points in the first

quadrant have positive values for both

Coördinates. — The corresponding

Straight Lines. — The student has no doubt observed

that all points plotted in the equation

100

enter the equation as a square or as a higher power; thus,

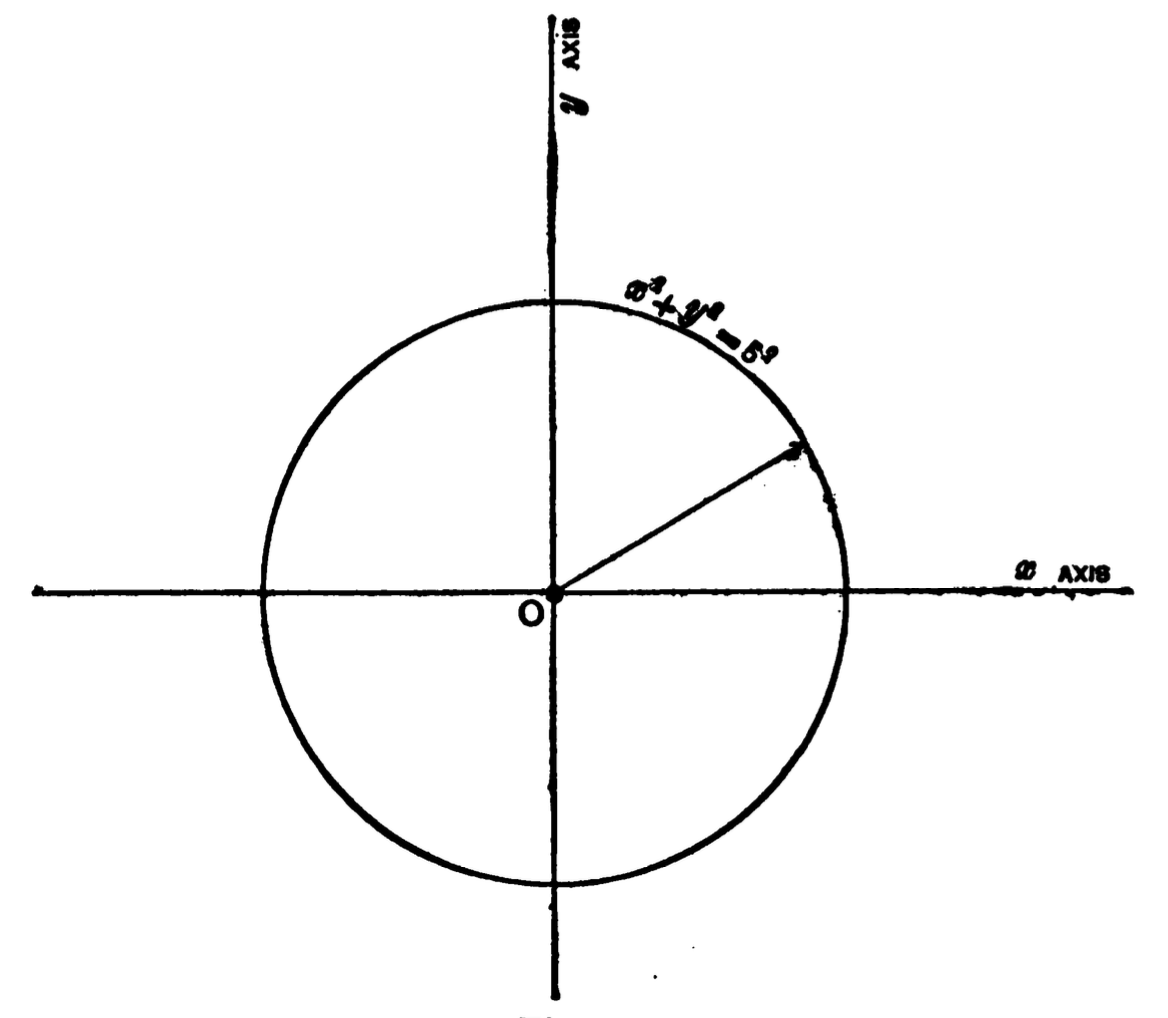

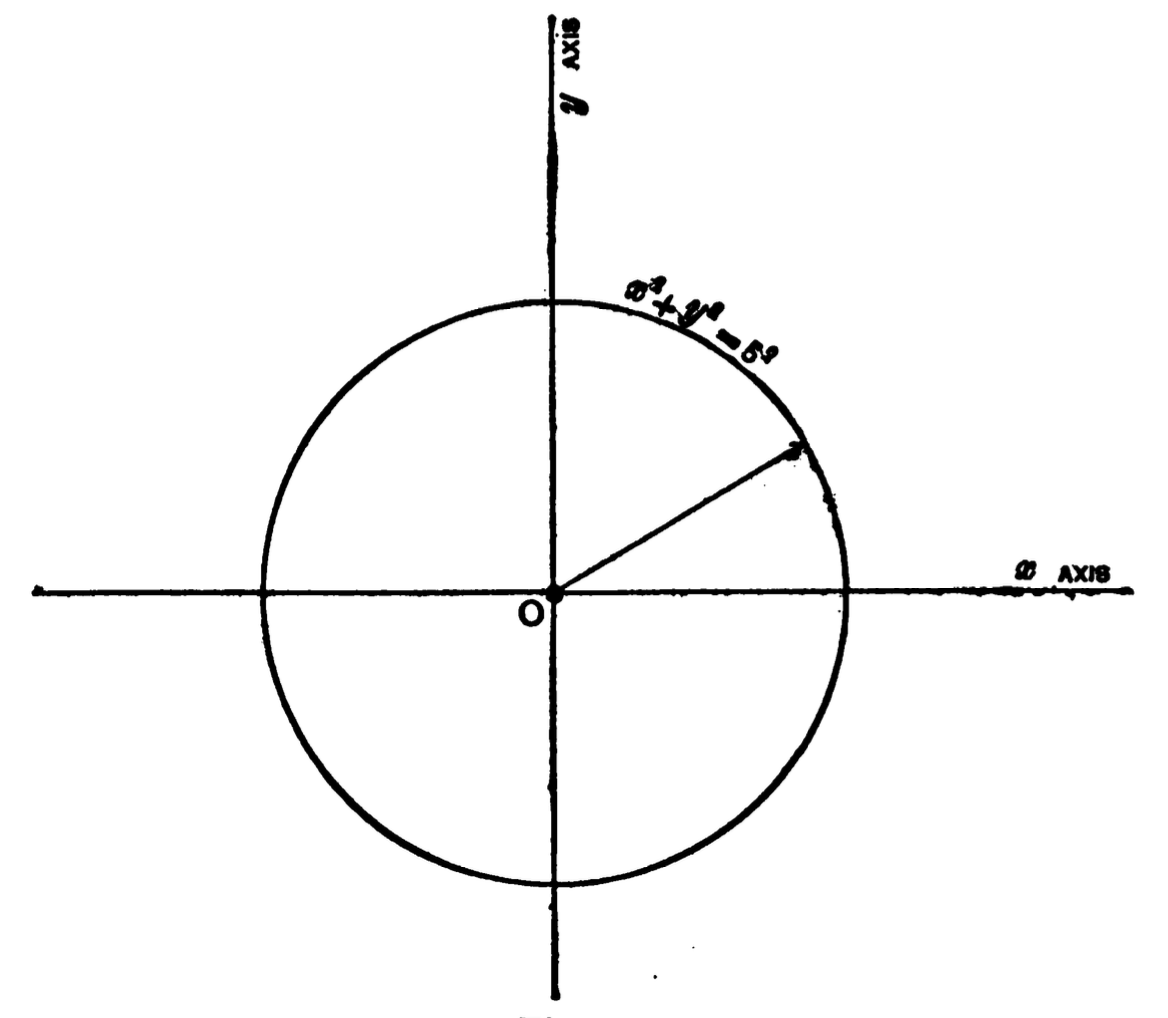

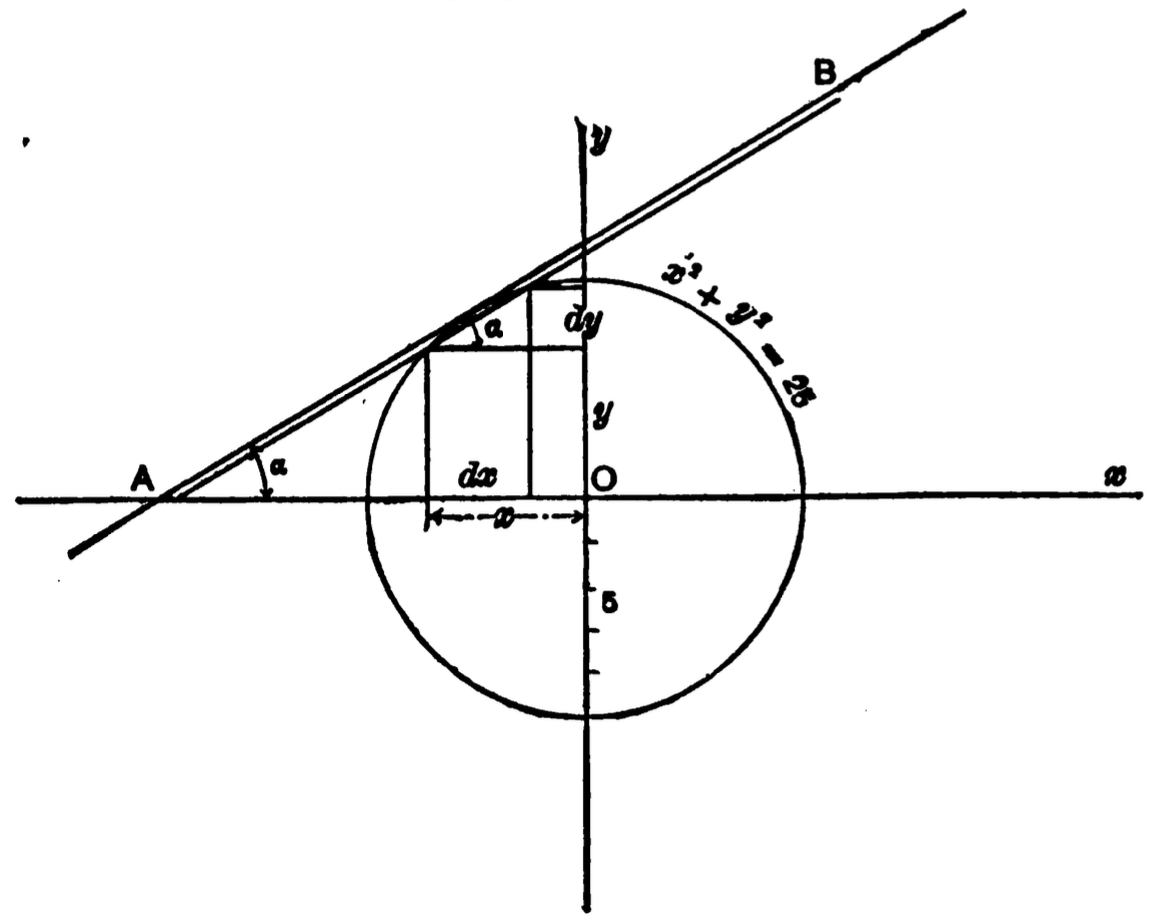

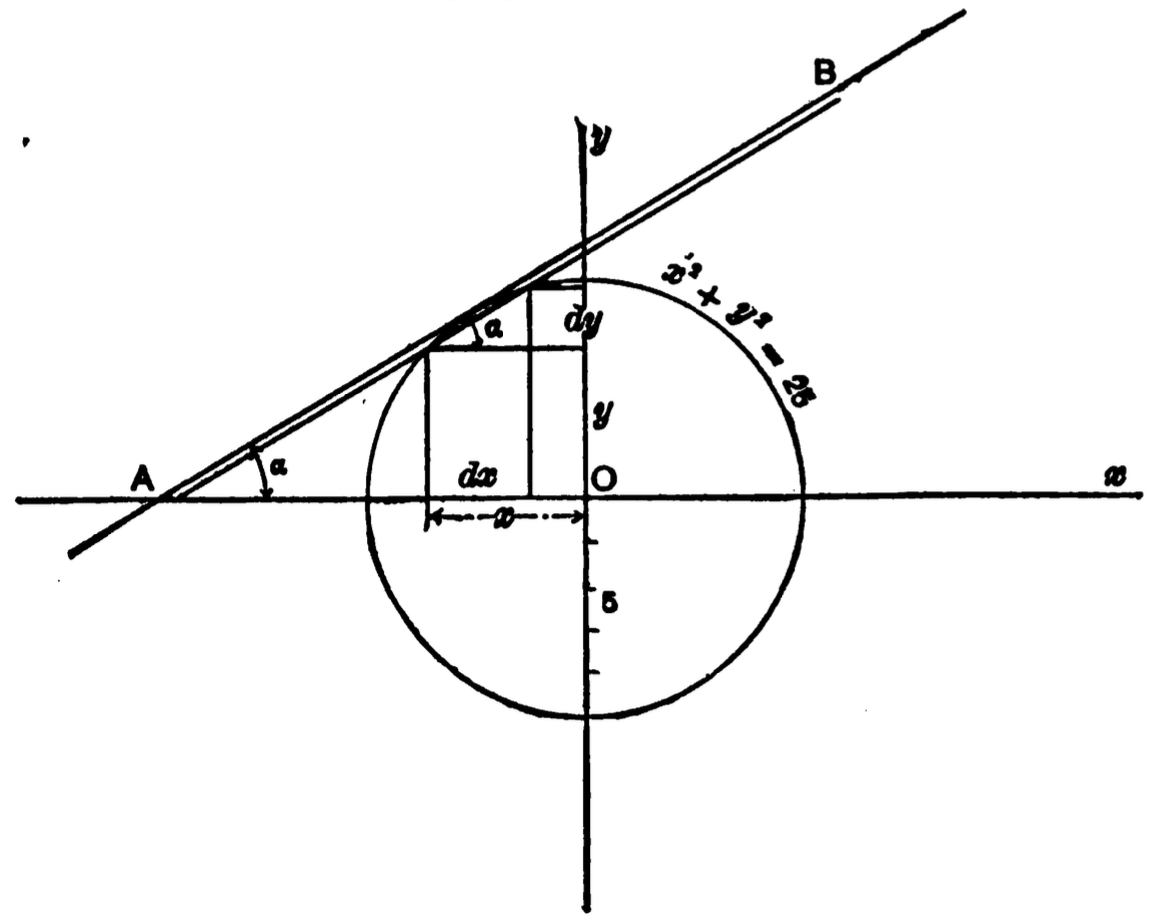

Conic Sections. — If either or both of the unknown

quantities enter into the equation in the second power,

and no higher power, the equation will always represent

one of the following curves: a circle or an ellipse, a

parabola or an hyperbola. These curves are called the

conic sections. A typical equation of a circle is

It is noted in every one of these equations that we

have the second power of

I have said that any equation containing

101

we have just given. But sometimes the equations do

not correspond to these types exactly and require some

manipulation to bring them into the type form.

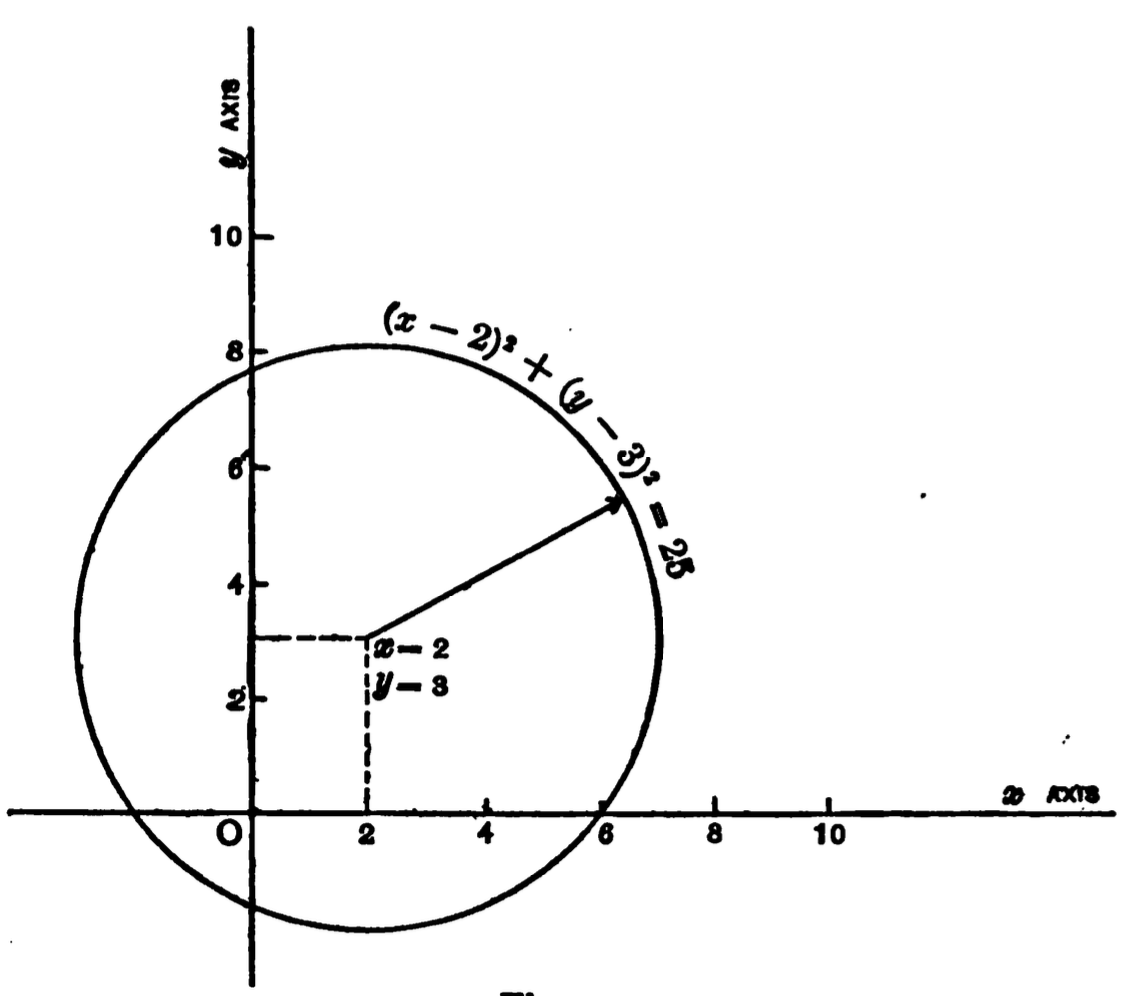

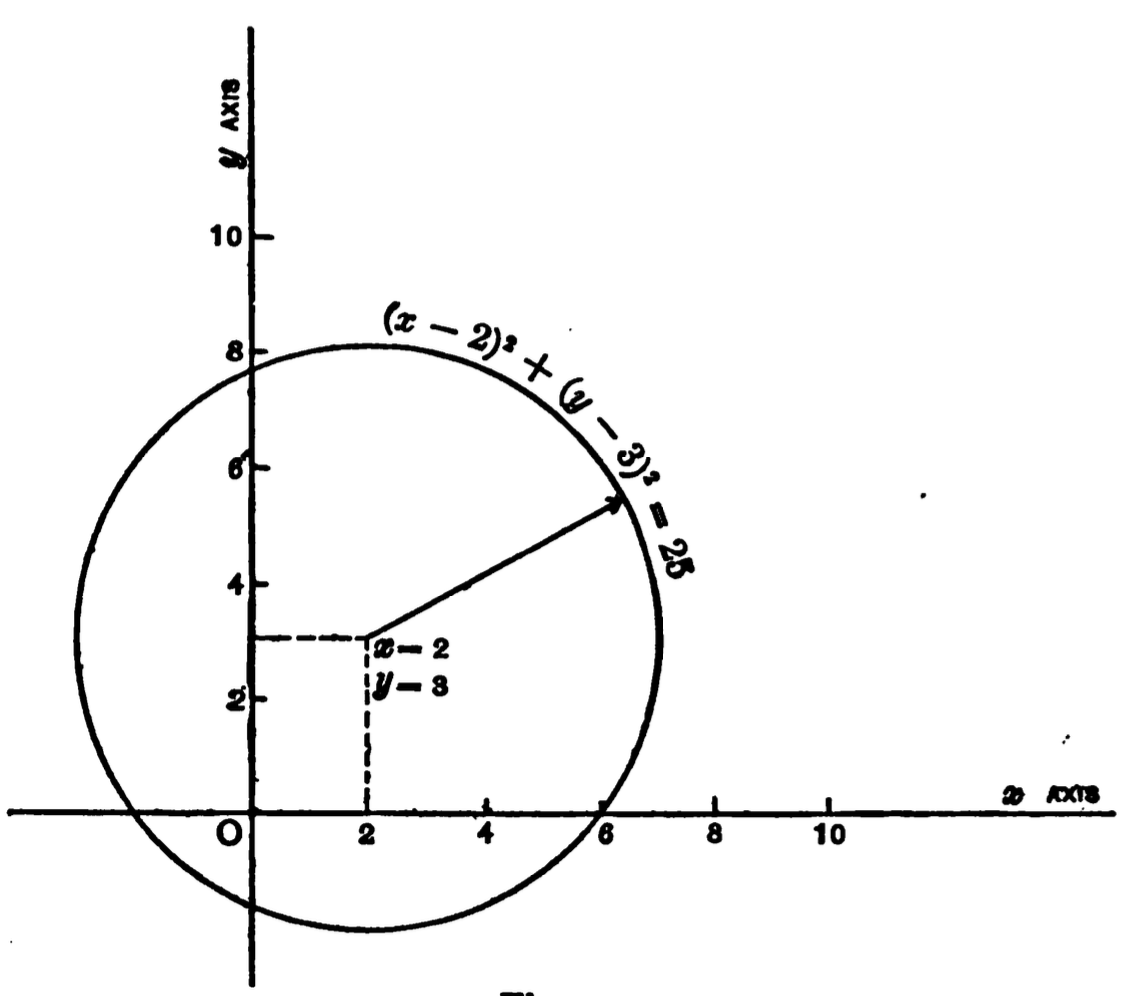

Let us take the equation of a circle, namely,

Fig. 29

Fig. 29

We see that it is a circle with its center at the intersection

of the coördinate axes. Now take the equation

Fig. 30

102

but frequently it is difficult at a glance to discover this

identity, therefore much ingenuity is frequently required

in detecting same.

Fig. 30

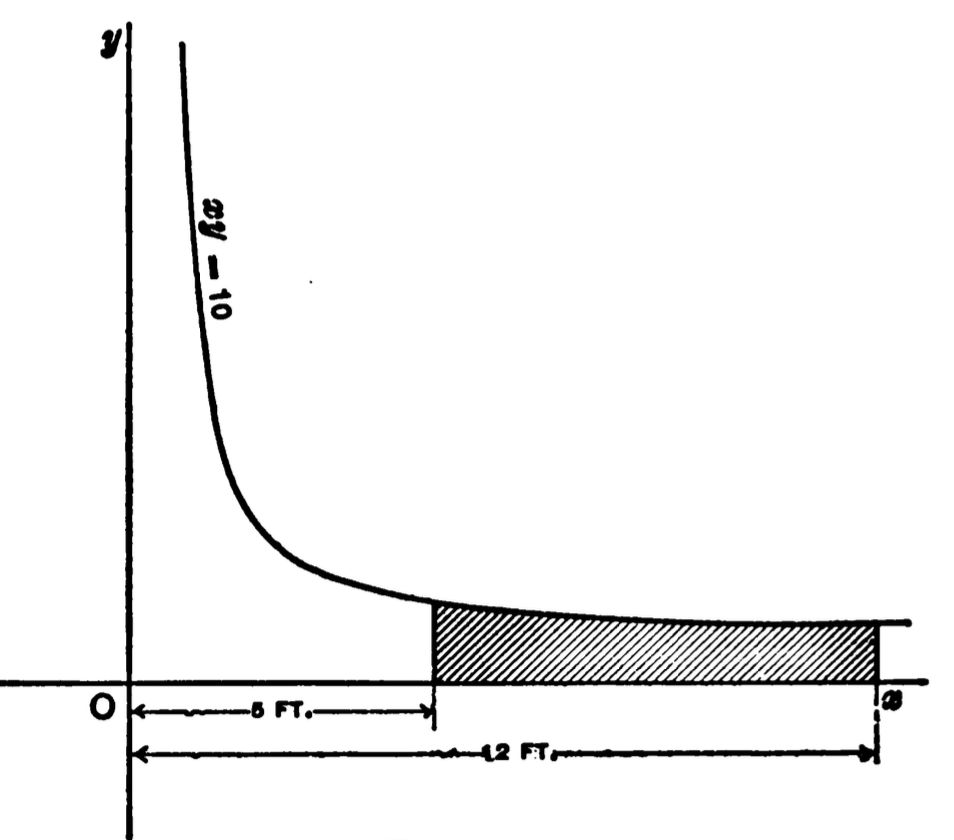

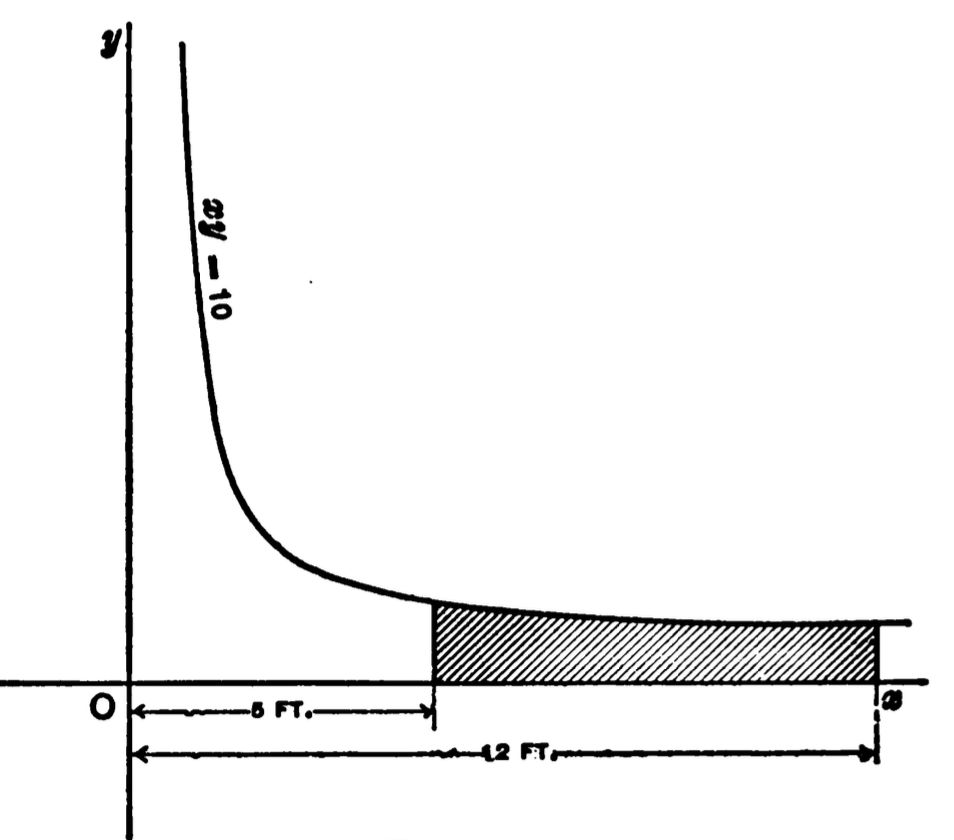

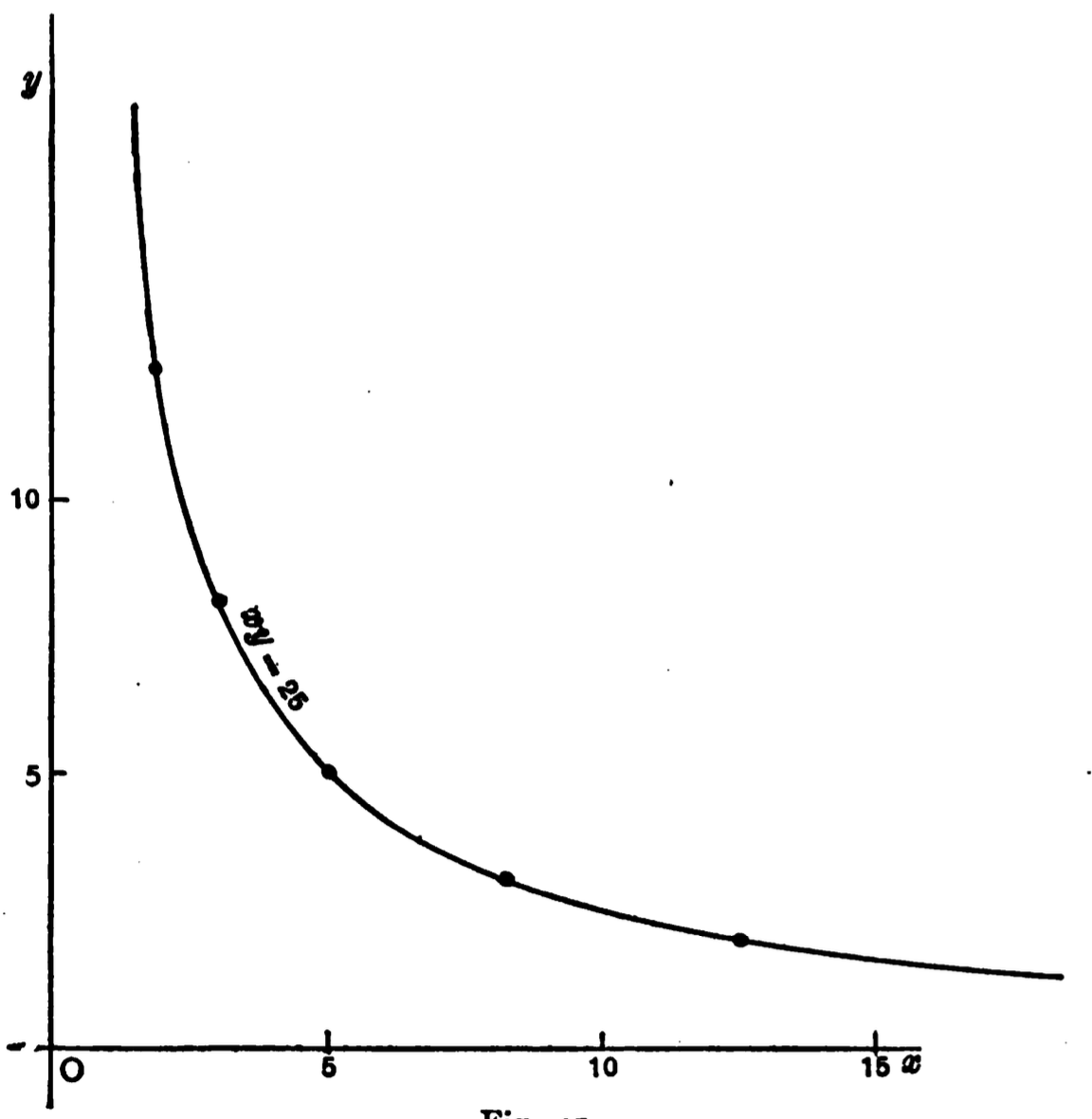

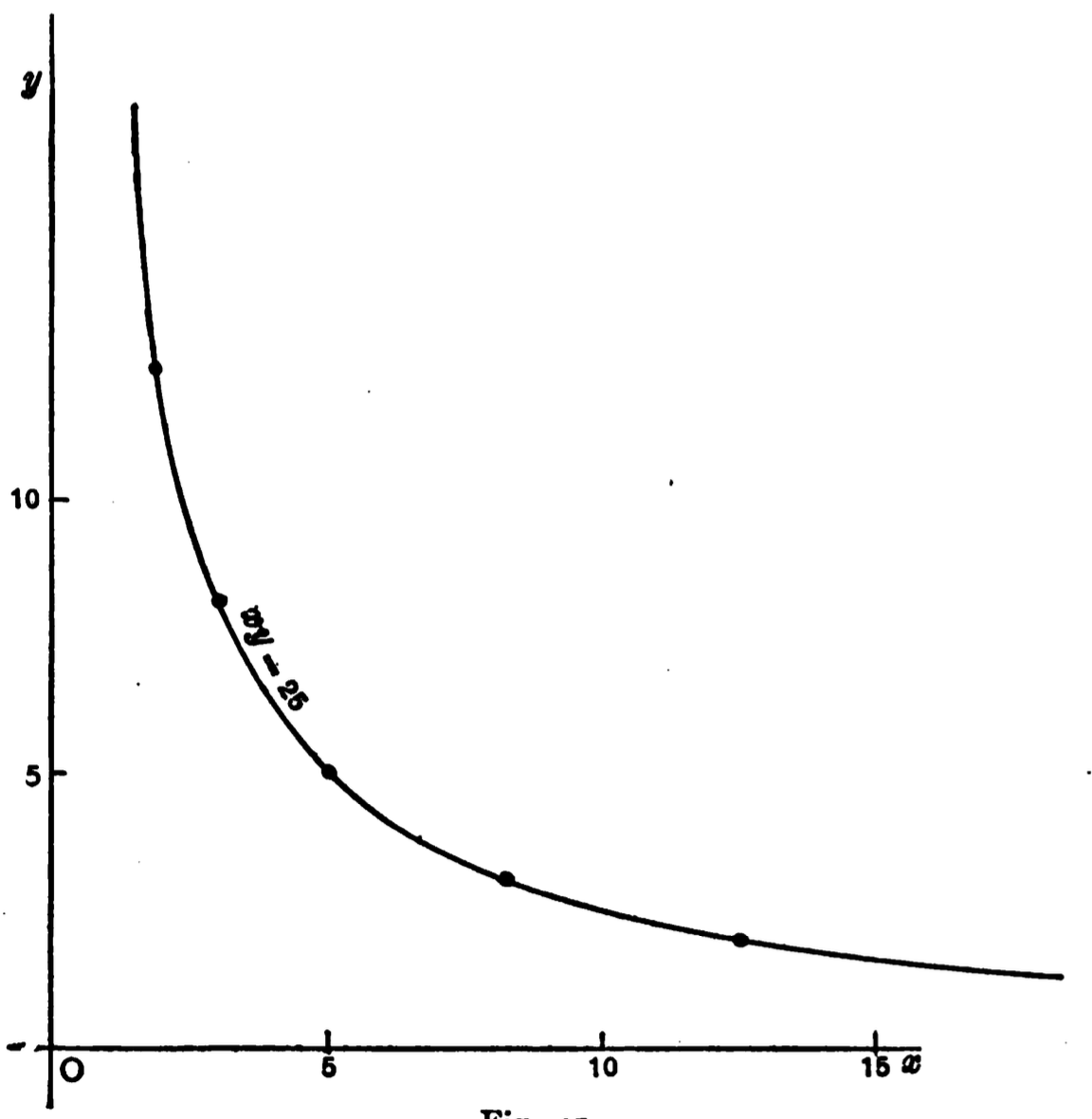

In plotting the equation of a hyperbola,

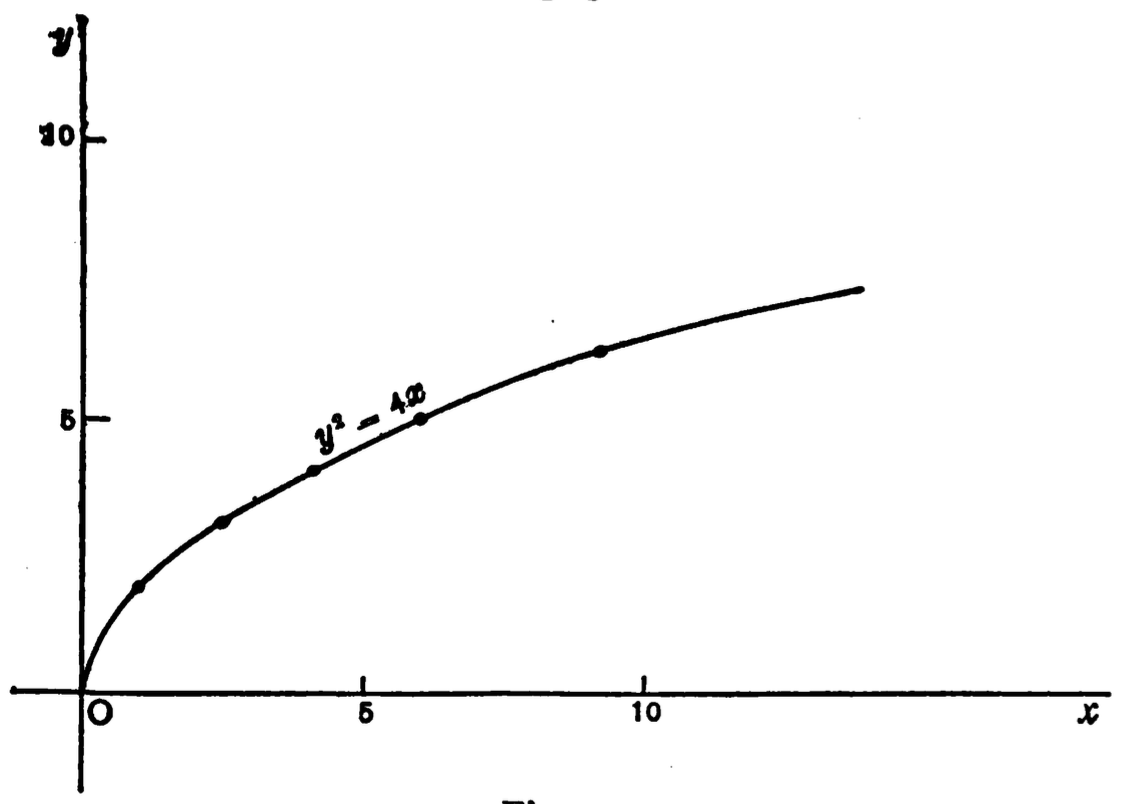

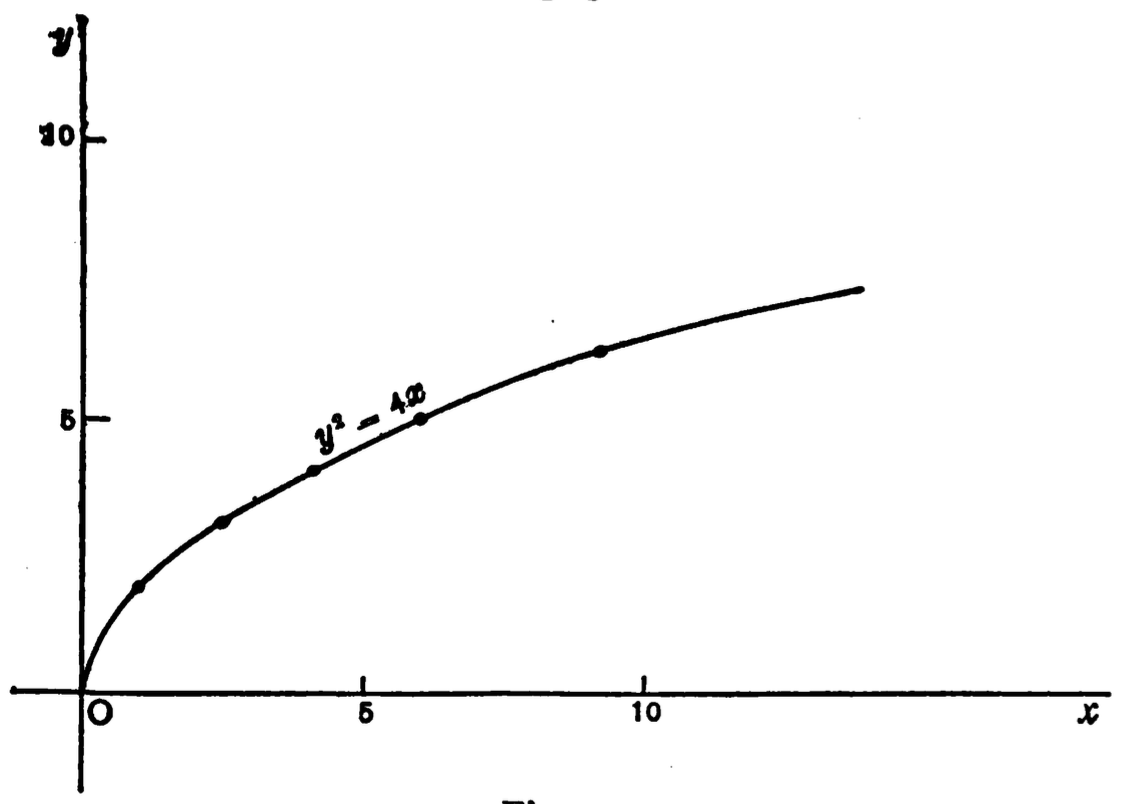

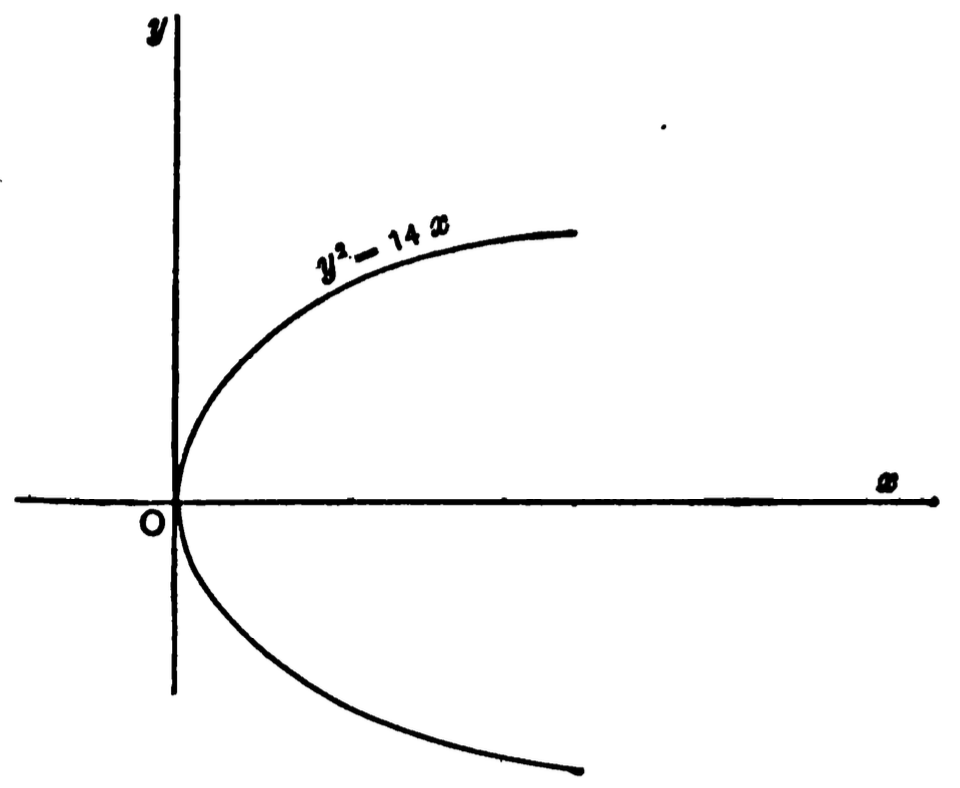

Similarly, in plotting a parabola (Fig. 32),

In this brief chapter we can only call attention to the

conic sections, as their study is of academic more than

Fig. 31

Fig. 32

103

Fig. 31

Fig. 32

104

of pure engineering interest. However, as the student

progresses in his knowledge of mathematics, I would

suggest that he take up the subject in detail as one

which will offer much fascination.

Other Curves. — All other equations containing unknown

quantities which enter in higher powers than the

second power, represent a large variety of curves called

cubic curves.

The student may find the curve corresponding to

engineering laws whose equations he will hereafter

study. The main point of the whole discussion of this

chapter is to teach him the methods of plotting, and if

successful in this one point, this is as far as we shall go

at the present time.

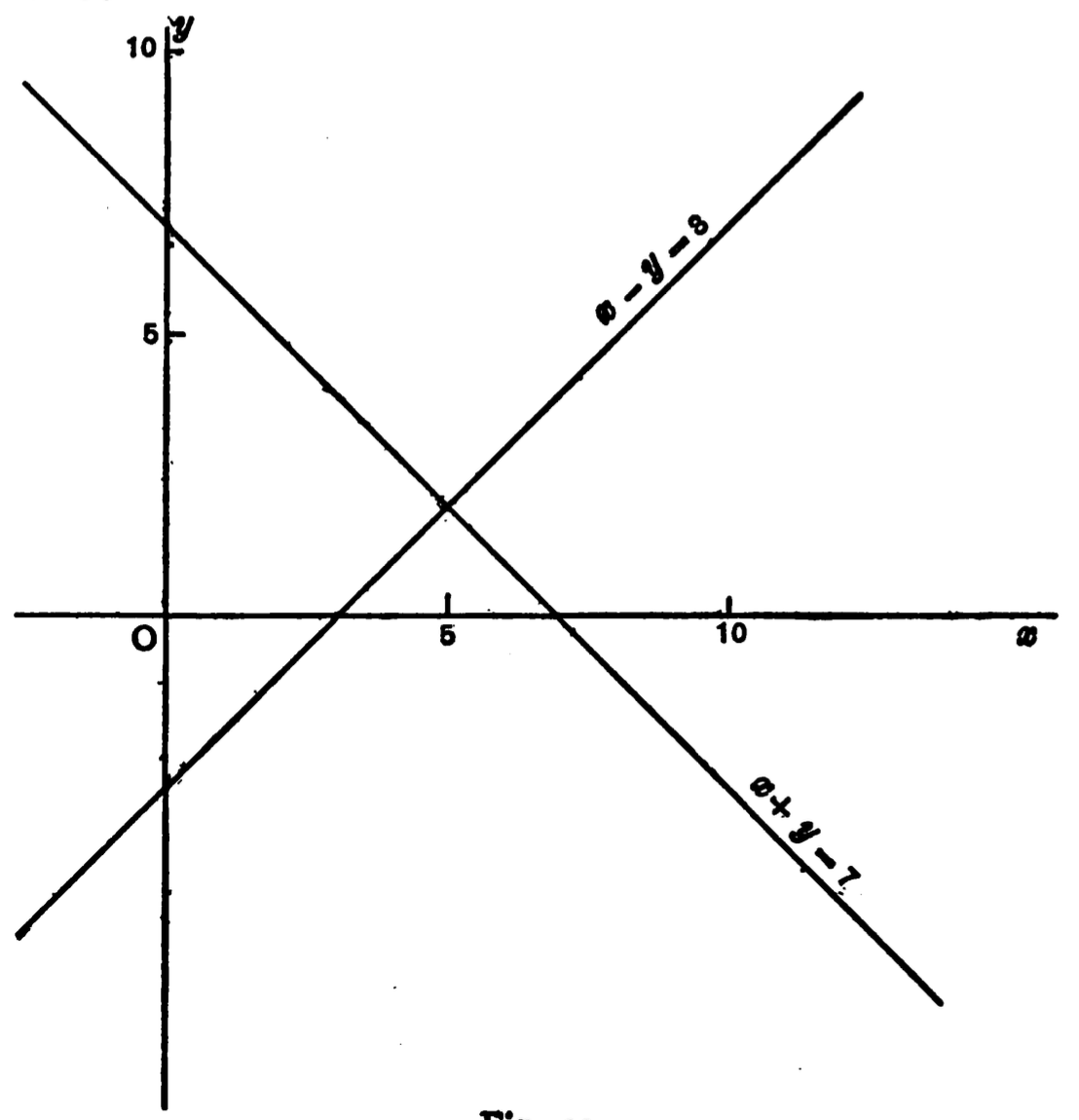

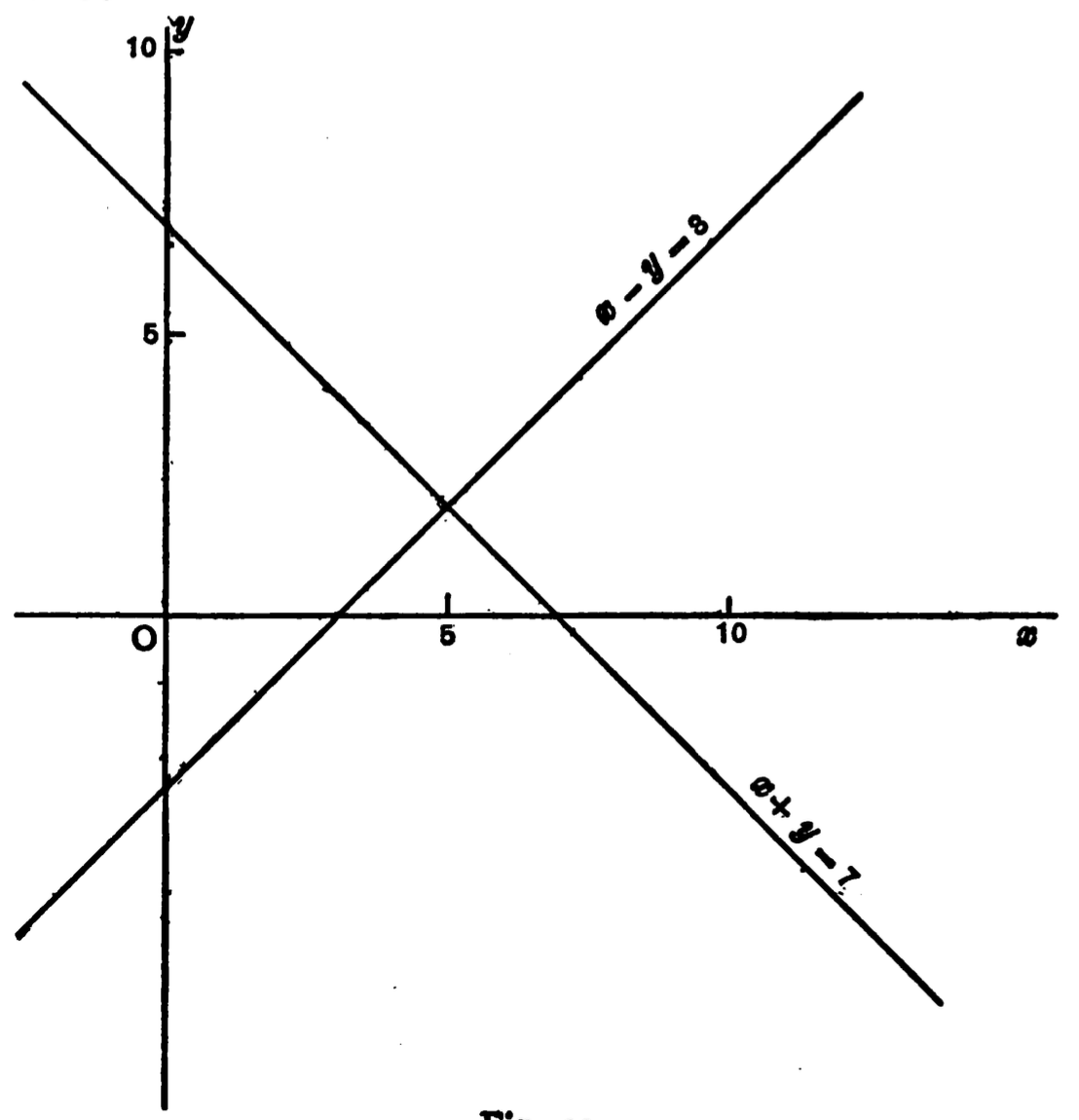

Intersection of Curves and Straight Lines. — When

studying simultaneous equations we saw that if we had

two equations showing the relation between two unknown

quantities, such for instance as the equations

,

.

we could eliminate one of the unknown quantities in

these equations and obtain the values of

,

.

105

Substituting this value of x in one of the equations, we

have

.

Now each one of the above equations represents a

straight line, and each line can be plotted as shown in

Fig. 33.

Fig. 33

Fig. 33

Their point of intersection is obviously a point on

both lines. The coördinates of this point, then,

106

have two equations each showing a relation in value

between the two unknown quantities, x and y, by combining

these equations, namely, eliminating one of the

unknown quantities and solving for the other, our

result will be the point or points of intersection of both

curves represented by the equations. Thus, if we add

the equations of two circles,

,

,

and if the student plots these equations separately and

then combines them, eliminating one of the unknown

quantities and solving for the other, his results will be

the points of intersection of both curves.

Plotting of Data. — When plotting mathematically

with absolute accuracy the curve of an equation, whatever

scale we use along one axis we must employ along

the other axis. But, for practical results in plotting

curves which show the relative values of several varying

quantities during a test or which show the operation

of machines under certain conditions, we depart

from mathematical accuracy in the curve for the sake

of convenience and choose such scales of value along

each axis as we may deem appropriate. Thus, suppose

we were plotting the characteristic curve of a shunt

dynamo which had given the following sets of values

from no load to full load operation:

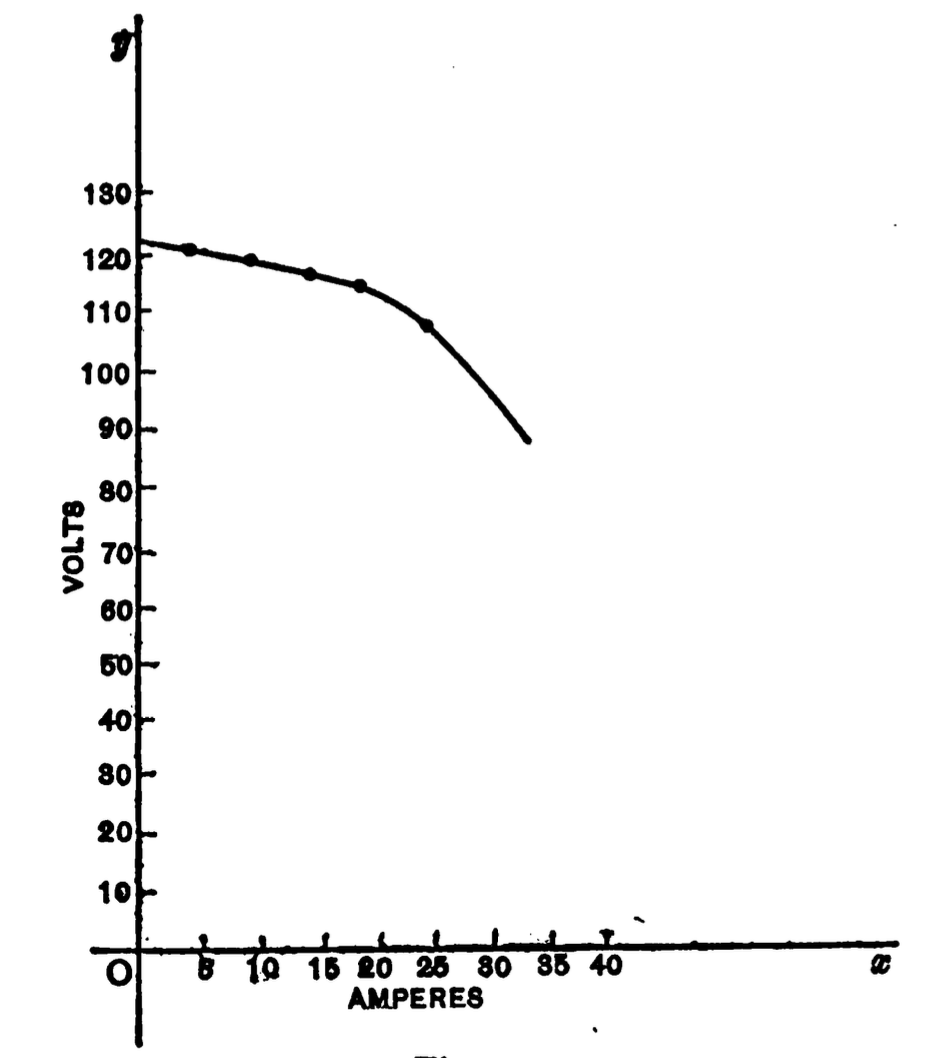

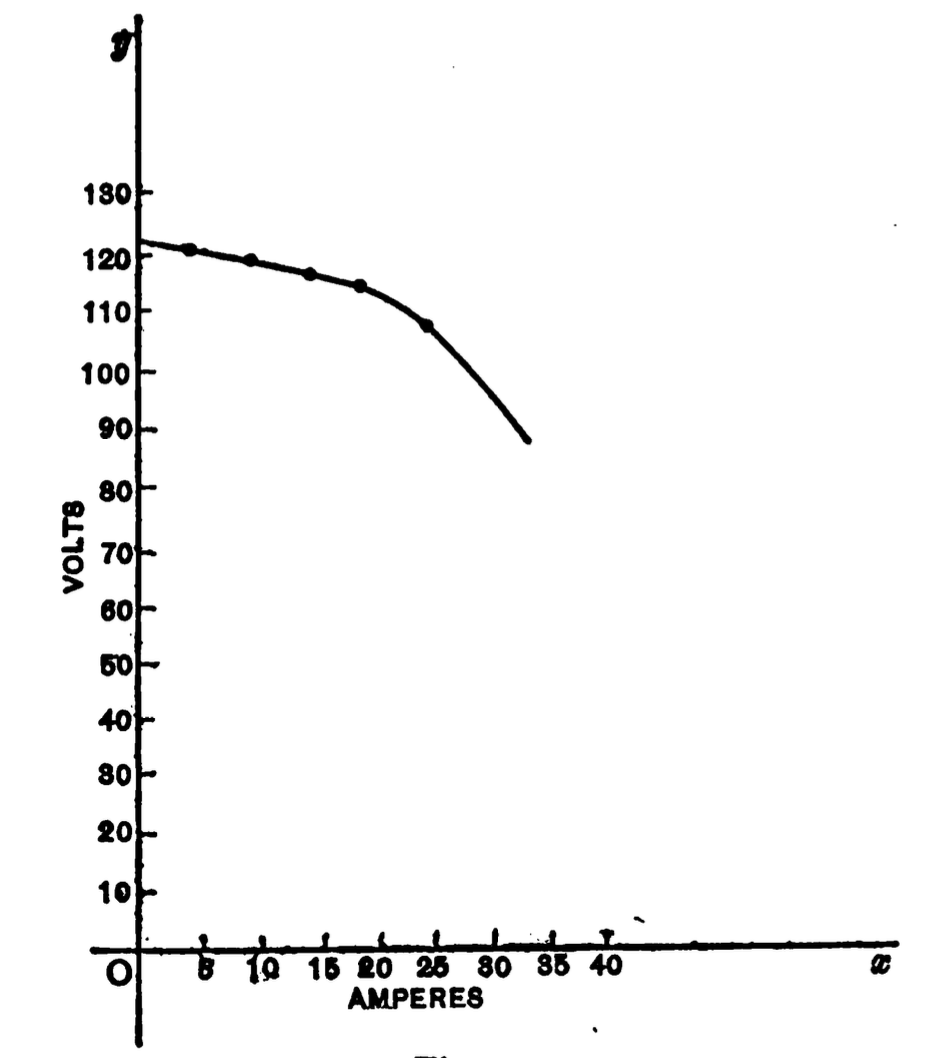

Fig. 34

107

| VOLTS | AMPERES |

| 122 | 0 |

| 120 | 5 |

| 118 | 10 |

| 116 | 15 |

| 114 | 19 |

| 111 | 22 |

| 107 | 25 |

Fig. 34

We plot this curve for convenience in a manner as

shown in Fig. 34. Along the volts axis we choose a

scale which is compressed to within one-half of the

108

space that we choose for the amperes along the ampere

axis. However, we might have chosen this entirely at

our own discretion and the curve would have had the

same significance to an engineer.

PROBLEMS

Plot the curves and lines corresponding to the following

equations:

1..

2..

3..

4..

5..

6..

7..

8..

Find the intersections of the following curves and

lines:

1.,

.

2.,

.

3.,

.

109

Plot the following volt-ampere curve:

CHAPTER XIV

| VOLTS | AMPERES |

| 550 | 0 |

| 548 | 20 |

| 545 | 39 |

| 541 | 55 |

| 536 | 79 |

| 529 | 91 |

| 521 | 102 |

| 510 | 115 |

110

CHAPTER XIV

Elementary Principles of the Calculus

It is not my aim in this short chapter to do more

than point out and explain a few of the fundamental

ideas of the calculus which may be of value to a

practical working knowledge of engineering. To the

advanced student no study can offer more intellectual

and to some extent practical interest than the advanced

theories of calculus, but it must be admitted

that very little beyond the fundamental principles ever

enter into the work of the practical engineer.

In a general sense the study of calculus covers an investigation

into the innermost properties of variable quantities,

that is quantities which have variable values as

against those which have absolutely constant, perpetual

and absolutely fixed values. (In previous chapters we

have seen what was meant by a constant quantity and

what was meant by a variable quantity in an equation.)

By the innermost properties of a variable quantity we mean

finding out in the minutest detail just how this quantity

originated; what infinitesimal (that is, exceedingly small)

parts go to make it up; how it increases or diminishes

with reference to other quantities; what its rate of

increasing or diminishing may be; what its greatest

111

and least values are; what is the smallest particle into

which it may be divided; and what is the result of

adding all of the smallest particles together. All of

the processes of the calculus therefore are either analysis

or synthesis, that is, either tearing up a quantity

into its smallest parts or building up and adding

together these smallest parts to make the quantity.

We call the analysis, or tearing apart, differentiation;

we call the synthesis, or building up, integration.

DIFFERENTIATION

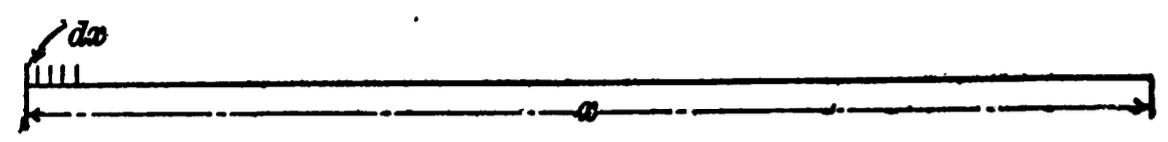

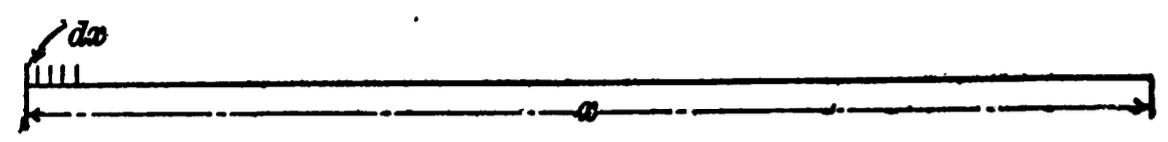

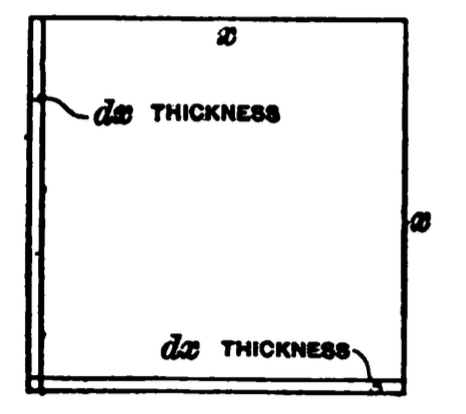

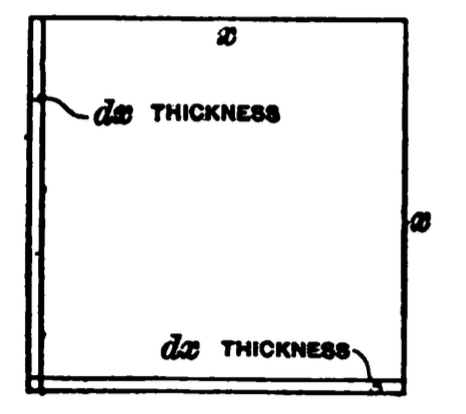

Suppose we take the straight line (Fig. 35) of length

Fig. 35

Fig. 35

have any conception, we say that each part is infinitesimally

small,—that is, it is small beyond conceivable

length. We represent such inconceivably small lengths

by an expression

112

We have seen that the differential of a line of the

length

Fig. 36

of each side by an infinitesimally small amount,

Fig. 36

= additional area.

(The student should note this very carefully.) Therefore

the addition equals

= additional area.

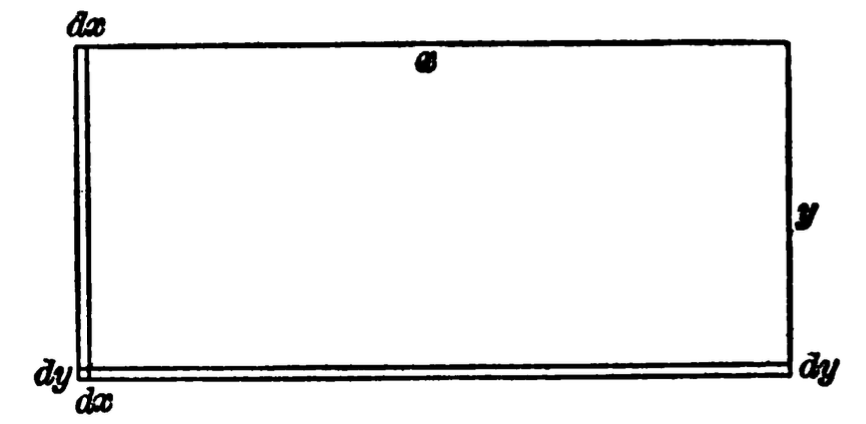

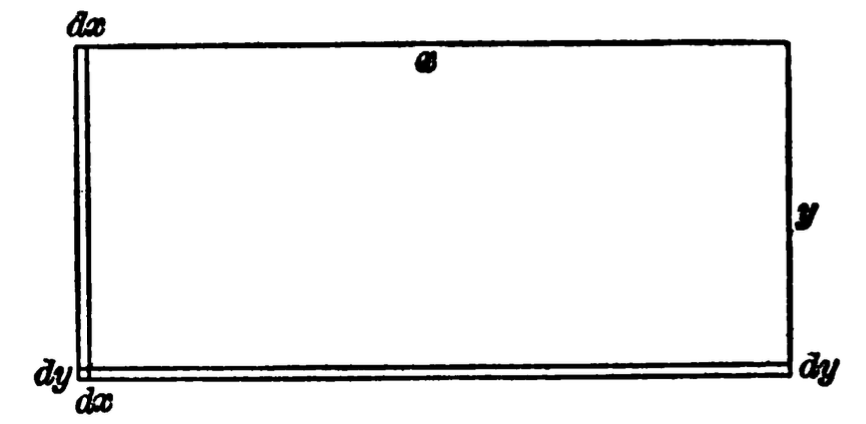

Now the smaller

113

proportion does

Again, if we reduce the side

differential of,

differential of,

differential of,

differential of.

114

From these we see that there is a very simple and definite

law by which we can at once find the differential of

any power of

Law. — Reduce the power of

I will repeat here that it is necessary for the student

to get a clear conception of what is meant by differentiation;

and I also repeat that in differentiating any

quantity our object is to find out and get the value of

the very small parts of which it is constructed (the rate

of growth). Thus we have seen that a line is constructed

of small lengths

Differentiation Similar to Acceleration. — We have just

said that finding the value of the differential, or one of

the smallest particles whose gradual addition to a quantity

makes the quantity, is the same as finding out the

rate of growth, and this is what we understood by the

ordinary term acceleration. Now we can begin to see

concretely just what we are aiming at in the term

differential. The student should stop right here, think

over all that has gone before and weigh each word of

115

what we are saying with extreme care, for if he understands

that the differentiation of a quantity gives us

the rate of growth or acceleration of that quantity he

has mastered the most important idea, in fact the keynote

idea of all the calculus; I repeat, the keynote idea.

Before going further let us stop for a little illustration.

Example. — If a train is running at a constant speed

of ten miles an hour, the speed is constant, unvarying

and therefore has no rate of change, since it does not

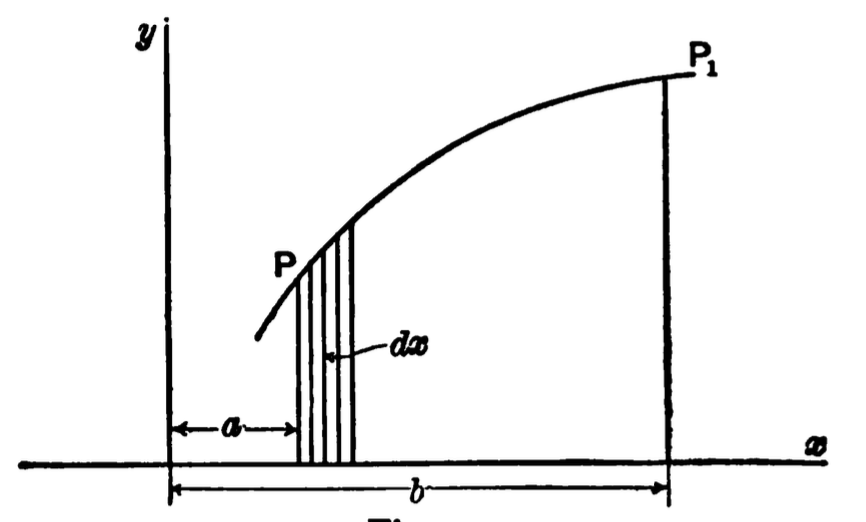

change at all. If we call